I was going to post some colour photos I found the other day of the confrontation in front of the provincial hall on May 21, 1980 that ended with troops opening fire on Kwangju's citizens, but then, after I thought of adding some commentary, the post turned out much longer than I'd planned. I suppose as a prelude to this post reading my posts about those who were

randomly beaten by paratroopers on May 18, as well as the

escalation of violence over the first three days of the uprising might be helpful, as they chronologically lead into this post.

May 20 and 21 saw the scattered protests of the previous two days become larger, despite the fact that for the first three days, more troops were sent into the city each day; by May 20, 3000 paratroopers were in the city. And yet the citizens of Kwangju would not only stand up to them, but by the evening of the 21st, force them out of the city, though at great cost.

Jung-woon Choi's essay 'The Formation of an "Absolute Community"' from the book

Contentious Kwangju describes the events of May 20:

[On] the morning of May 20... a corpse was discovered in front of the Chonnam Brewing Company. Enraged citizens gathered in front of the Taein Market and began to demonstrate. In the afternoon, large numbers of citizens - men, women, the elderly, the young - slowly began to come in from the outskirts of the city and gathered in the downtown area. A large demonstration shortly ensued. At approximately 2:30 pm, paratroopers began firing flamethrowers at the Seobang intersection. Several citizens were burned to death on the spot. The citizens became extremely agitated. Around 3 pm, the Seventh and Eleventh Brigades were redeployed in the downtown area. An all-out battle between the citizens and paratroopers broke out.[...]

In front of Hwani Department Store on Geumnam avenue, a student gave a speech, led in chanting slogans, and read from leaflets. When it became difficult to hear the speaker's voice, someone began taking up a collection to purchase a loudspeaker, and a sum of 400,000 won was collected on the spot.

Choi marks this as an example of the beginning of an "absolute community", where "there were no private possessions, and citizens did not differentiate their lives from that of others." Choi would go on to examine this further in his fascinating book

The Sociology of the Kwangju Uprising (오월의 사회과학, 1999), translated into English as

The Gwangju Uprising. Whether you subscribe to his description of an absolute community or not, it should be pointed out Kwangju was a relatively small city where, within a few days, almost everyone knew someone who had been hurt by the paratroopers, and because of this many began to take part in demonstrations or support those who were demonstrating. On May 20, the individual, separate protests that had been appearing around the city for the past three days began to coalesce into larger and more organized demonstrations, with people sharing food and building barricades. The most obvious example of this developing community spirit was the fact that taxi drivers mobilized a vehicle demonstration, using their means of livelihood - their cars - to protest with, likely knowing full well that they would not be left unscathed.

That afternoon, taxi drivers in front of Kwangju station had traded stories of the abuse other drivers had faced while trying to help injured demonstrators get to hospitals, and decided to take part in the demonstrations. The organized the other drivers and 200 taxis followed several buses downtown, arriving near the provincial hall around 7:00.

At that point the demonstrators, who thought at first they might be army vehicles, were emboldened by their presence, and joined the drivers.

The paratroopers began to build barricades, and once the protesters reached the barricades, the paratroopers fired tear gas and charged, smashing in windows and revealing how precarious the drivers' position was, being unable to easily flee their vehicles.

As the deleted section of a May 22 Donga Ilbo article described it,

A moment later, amidst thick tear gas, the demonstrators, with buses in the lead, fought hand to hand with the soldiers, so that cries of pain and shouting were unceasing in the Chonil Broadcasting Company area near Kumnamno. When this clash ended after 20 minutes, there were bloody and unconscious casualties with broken heads and fractured limbs here and there among the buses, trucks, and taxis. Two young women in their twenties, dressed in guide uniforms, were wailing and holding a man in his thirties in a driver's outfit with a broken head. The choked voices of people carrying casualties asking to "quickly send ambulances for the critically injured," told of the atrocity of the bloodshed.

Choi points to the drivers' participation as a unifying moment. Encouraged by the drivers' solidarity, and urged on by street broadcasts, more and more angry citizens gathered in the streets, hemmed in the paratroopers in several locations and began attacking the soldiers' barricades with cars, some of which were set on fire. In front of the Regional Labor Administration, four police officers were killed when a car driven by a protester plowed into their lines. This may have been due to the driver being blinded by teargas. While it may seem a convenient excuse, these were the only police killed during the uprising, and police were rarely the targets of the citizens' rage, which was almost exclusively reserved for the paratroopers. By the end of the night, MBC and KBS were set on fire (its often said by the demonstrators, but the possibility exists that the soldiers did it, not wanting the protesters to gain access to the facilities). The tax office also went up in flames. These places were abandoned by the paratroopers.

The presence of 30,000 demonstrators who were increasingly fighting together, led to this, as described in Choi's book:

After midnight, paratroopers and police began to use a respectful form of speech through speakers, instead of the high-handed, commanding tone they had used before. They said, "Please return to your homes were your parents and siblings are waiting. At your homes, your families are worried about you because you have not come home yet."

Another battle took place near Kwangju Station, which the military was determined to hold because of its importance for the transportation of troops and supplies. Some protesters tried to charge the soldiers with cars, leading to the first large scale shooting incident, as related by a paratrooper, Kim Yong-jin, who arrived there as a reinforcement sent from the 3rd Brigade headquarters at Chonnam University:

While advancing, a major, an operations staff member of the 3rd Brigade, held up a gun shouting: "I will shoot you to death if you retreat," so that we reached the area near Kwangju Station in terror. When we arrived at Kwangju station, soldiers were standing in a single line in front of the train station building, shooting ceaselessly, and near the fountain buses and trucks carrying citizens had driven into the fountain while charging at the soldiers. One sergeant, a vehicle driver of the 3rd Airborne Brigade, died after being run over by a truck, and about 20 citizens were abandoned near the fountain, drenched in blood.

Many of the demonstrators that had been arrested over the past three days were held in a gym at Chosun University, where they were being beaten regularly. Hearing of this, 3000 demonstrators headed to the university to free them, using buses to charge the gate. The soldiers successfully defended the university, but had to use hand grenades to do so. By daybreak the paratroopers could be found only on the two university campuses and at the provincial hall.

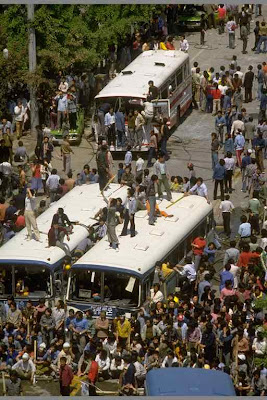

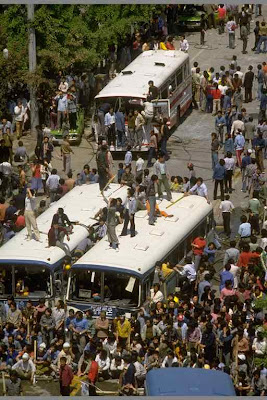

These photos may give some idea of how intense the fighting was.

Suh Chung-won, a Chosun Ilbo correspondent, describes his experience of the next day, May 21:

I heard that three [actually two] bodies had been found when the military evacuated Kwangju Station. The discovery of these dead had outraged the demonstrators[...] At 6am approximately 1000 protesters were gathered in the MBC building area, demonstrating at the intersections on Gumnam-ro. [...] Demonstrators appeared pushing a bicycle cart with two bodies on it. The citizens began to gather once more, as early as 7am.

The mood seemed a bit calmer. A group of demonstrators then appeared with trucks, bringing bread. They distributed food among the people. Then at about 8 am, Chun Ok-ju, thirty two, a woman leader well known at that time, made a speech. She urged the citizens to mourn for the dead and maintained that the demonstration was righteous. She proposed a meeting with the mayor of Kwangju.

Yi Se-yeong, who had taken part in demonstrations, but stayed home the 20th, described the situation on the morning of the 21st:

Wherever we went, women lifted seaweed-rolled rice and rice balls to our car, telling us to fight with courage. Sometimes they wiped our faces, smeared with tear-gas smoke, with wet towels. Women, in neighborhood units, prepared food and distributed it to us. From stores, people tossed us soft drinks and pastries.

Suh Chung-won continues:

From 9 am people gathered in larger numbers on Gumnam-ro. Meanwhile, some demonstrators had obtained armored cars and jeeps from the Asia Motors factory in the Kwangju industrial complex. They drove the vehicles into the downtown area around 10 am. Using the armored vehicles they began to press back the army lines. They pressed towards the Catholic center. Pepper fog and tear gas were useless to hold them back. From 10:30 am, as on the previous day, the demonstrators squeezed in toward the Provincial Hall from three sides.

Cho Sung-ho, a Hanguk Ilbo reporter, noted that

About 9 am a crowd of about 10,000 people confronted the paratroopers, protesting the atrocities committed by them between May 18 and May 20. By 10 am the crowd had swelled to 20,000 people or thereabouts.

On the roads leading to Gumnam-ro there were many people struggling desperately with the paratroopers. The latter fired tear gas indiscriminately.[...] Police helicopters announced overhead the words of the governor of South Cholla province and the Mayor of Kwangju - the region's top two dignitaries. Both called for order, using slogans such as "Citizens, let us save Kwangju!" Their announcements simply were not heard.

Suh Chung-won continues:

At noon a rumor began to spread that the demonstrators had occupied the Provincial Hall. Accordingly, the demonstrators at the Catholic center moved forward about 200 meters, with the armored cars and trucks leading the way.

They came within 10 meters of the army defense lines in front of the Kwangju Tourist Hotel. [...]

It was 12:30 pm.[...] A that moment a commandeered armored personnel carrier with a young man standing on it headed straight towards a line of soldiers in front of the Provincial Hall. He was shot and fell, as did several soldiers [one soldier died when the tracked army vehicle in front of him reversed over him]. That triggered an outburst of tear gas fire. For a moment, the demonstrators hesitated. The troops retreated back towards the fountain in the middle of the square in front of the Provincial Hall.

Kim Yong-taek, of the Donga-Ilbo, wrote that

I was looking down on the square with Chonnam provincial governor Chang Hyong-tae from the third floor corridor of the Provincial Government Building, when ammunition was being distributed to the paratroopers in front of the fountain at around 10:10 am. ... It was a little before 1 pm when an armored vehicle driven by demonstrators charged at the paratroopers' defense line, and the time when the demonstrating vehicle [a bus], which was allegedly shot at by the paratroopers, rushed in was not much later, at around 12:58. Straight after, at 1pm sharp, the Aegukka was suddenly heard, at which point the shooting began.

If there is one thing the many accounts of this moment agree on, it's that the shooting coincided with the playing of the national anthem. At a meeting of reporters in Kwangju, several reporters noted what they saw next:

Reporter C: I saw, right in front of me, a person who was hiding behind a wall. He was shot in the neck and died on the spot.

Reporter D: Yes, the paratroopers are deliberately shooting people from rooftops. At 2 in the afternoon they started shooting at anything that moved. Not even a shadow moves around Provincial Hall right now.

American missionary Martha Huntley, who worked at the Kwangju Christian Hospital, which was neither the largest nor closest hospital, describes the scene that followed:

In two hours our hospital alone received 99 wounded and 14 dead. Among the wounded was a 9 year old boy who was shot in the legs. Our first dead was a middle school girl; the second was a commercial high school girl who had donated blood at the hospital 15 minutes earlier and was shot by the troops when she was being returned home in a student vehicle. We received 5 patients with spinal cord injuries, many of whom will never walk again. One was 13 years old. We had patients who lost eyes, limbs, and their minds.

The experience of a nurse at that same hospital can be found

here.

As Suh Chung Won continues,

Thereafter, from 3:40 pm onward, the situation was indistinguishable from wartime. Some demonstrators, who had obtained weapons, started shooting back at the soldiers. This was street fighting. At 4 pm I received a message saying that demonstrators had acquired weapons from an armory in Hwasun and were heading for downtown Kwangju in trucks.[...] As was revealed later, demonstrators were flocking back toward downtown Kwangju with weapons they had acquired in such places as Jangsong, Naju, Hwasun, and Damyang.

As to why it was necessary to leave the city to find weapons, Suh notes that "the army had already taken away all the weapons from the Provincial Hall, from police stations, and from police strong points the day before."

Peace Corps Volunteer David Dolinger

described the scene in Kwangju after returning to the city on the afternoon of the 21st.

As we neared downtown I heard a helicopter approaching, with its approaching sound I saw the people in the streets running for cover. I was told that they, the troops had been flying over since the morning and shooting into any crowds that they spotted. I then saw it for myself. As the helicopter flew over downtown I saw a soldier lean out of the side door and fire his gun. On Thursday I would visit the major hospitals where I would see those wounded by the fire from the helicopters. All had wounds of the upper torso with the projectile’s trajectory going downwards.

When I reached downtown I saw the side streets of Geum Nam Ro jammed with people. The martial law troops were massed in front of the Provincial Office Building.

From Geum Nam Ro sporatic gunfire could be heard. As I neared I saw that the people were no longer venturing on to Geum Nam Ro but were huddled in the side streets peering around the edges of the buildings. When I peered around the corner I saw a tank parked in front of the Gwangju Bank opposite of the CheIl Bank. The troops were also shooting up the street so as to keep everyone off of Geum Nam Ro. In addition, the machine gun on the tank was being fired. The gunfire was sporadic and did not seem to be directed at anyone.

What Dolinger saw may have been the paratroopers preparing a line of retreat.

Cho Sung Ho described the end of the battle:

At 4:40 pm, demonstrators finally set fire to their trucks and pushed them forward. Paratroopers who had held out now retreated hurriedly. (The paratroopers looked as if they were retreating under attack, in fact they had already been ordered to retreat by 4 pm.) Demonstrators finally entered the Provincial Hall. It was 5:30 pm.

Another large battle occurred in front of Chonnam university, where, as at Choson University, many of the arrested demonstrators were being held. Some 50,000 demonstrators fought with paratroopers at the front and rear gates. When commandeered police tear gas vehicles approached the paratroopers, the soldiers opened fire, killing several demonstrators and wounding many more.

The Military retreated from the center of the city. The 11th and 7th Brigades retreated to Chosun University and then to Jiwon-dong southeast of the city, while the 3rd Airborne Brigade retreated from Chonnam University to the nearby Kwangju Prison, in the northeast of the city. As the troops left Chosun University in a convoy of trucks following armored vehicles, numerous people were killed or wounded when the troops opened fire at random (One such victim is looked at

here).

As Linda Lewis notes, the 21st was

the bloodiest single day of the Kwangju Uprising. There were 62 official dead, most (54) killed by gunshot, the majority (66%) in the vicinity of the Provincial Office Buildings.[...] Most of the casualties on May 21 were unarmed citizens, shot down as troops fired repeatedly into crowds of demonstrators gathered downtown and in front of the Chonnam University gate.

Once the troops were on the outskirts of the city, more than 50 people would die at their hands, something I'll look at soon[er or later]. Six days after retreating from the city, the military would return, ending the uprising.