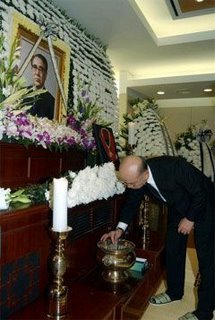

As everyone is aware, I'm sure, former president Choi Gyu-ha died Sunday morning. I was well aware of the part he played (or, to put it bluntly, didn't play) in the period following Park Chung-hee's death, when he became acting president, and Chun Doo-hwan's inauguration. In between these two events, of course, were the 12.12 'incident' ("a coup in all but name," as US ambassador William Gleysteen termed it) and the Kwangju uprising. Among the tributes and photos of people lighting incense (such as Chun Doo-hwan himself), was information on his background as a career bureaucrat, as well as the fact that he refused to testify in court during the 1996 trial of Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo. I've seen some criticism of him for "taking secrets to the grave", which I have to admit confuses me; other principal actors involved in the two main controversies, that of the 12.12 coup and Choi's resignation are still alive, namely Chun Doo-hwan - so why is Choi getting singled out? Perhaps for not standing up and speaking out at crucial moments, something that seemed to plague his presidency.

Both then US ambassador Gleysteen and USFK commander John A. Wickham have written about that time period (their books are listed here); Wickham's book may well be the most comprehensive source in English regarding the 12.12 coup.

Choi was appointed prime minister in 1975, and, upon Park Chung-hee's assassination by KCIA head Kim Jae-gyu on October 26, 1979, he became acting president. The night of Park's death, ROK army chief of staff Chung Sung-hwa had also been invited by Kim to dinner, and after the deed was done, Kim tried to convince Chung to come to KCIA headquarters. Chung instead convened a meeting at the army headquarters bunker where it was finally established that Kim Jae-gyu had been the shooter, leading to his arrest. It was there that Choi took on his responsibility as acting president. It was also there that he made the decision to appoint major general Chun Doo-hwan, commander of the Defense Security Command, to investigate Park's death. As Wickham described it,

Chun was ambitious and suspicious of Chung and his reasons for being present the night of the assassination (which still aren't clear today, though he was eventually exonerated of any wrongdoing). Unlike everyone else involved, Chung, as head of martial law command, could not easily be interviewed. Meanwhile, Choi was now acting president, and was trying to move towards political liberalization with difficulty. As Gleysteen described him,

And there were lots of challenges. For the first time in years, as restrictions began to lift, people could take part in the political realm. This led to Choi having to navigate a course between headstrong radicals who wanted democratic freedoms yesterday, opportunistic politicians vying for power, and groups in the military who feared losing their influence.

And there were lots of challenges. For the first time in years, as restrictions began to lift, people could take part in the political realm. This led to Choi having to navigate a course between headstrong radicals who wanted democratic freedoms yesterday, opportunistic politicians vying for power, and groups in the military who feared losing their influence.

Meanwhile, Chun had found out his ambition had not gone unnoticed, and that he and a number of his friends would soon be demoted or transferred, which led him to use Capital Security Command troops, as well as Special Forces brigades, to seize Seoul and arrest Chung. The conspirators also moved elements of Roh Tae-woo's 9th division from the DMZ into Seoul, circumventing the chain of command and angering Wickham when he found out. At that point, however, what was happening was not clear to the Americans or to defense minister Rho Jae-hyun and ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff Kim Chung-hwan, who had made their way to a US bunker at Yongsan to confer with Wickham, who relates that

Rho and Kim, eventually get into phone contact with Chun Doo-hwan, whose demands left them with a sinking feeling:

Rho and Kim, eventually get into phone contact with Chun Doo-hwan, whose demands left them with a sinking feeling:

Wickham suggested Rho and Kim stay at the US command bunker until dawn, which they agreed to at first, but were soon convinced by the vice-minister of defence that the minstry of defence headquarters, a short distance away, was safe. As soon as they arrived, Chun's troops attacked the building and took Rho to the Blue House, where he eventually agreed to approve (after the fact) Chun's arrest of Chung and remove several other generals from command. After this, Choi "formally acquiecsed as well".

After the 12.12 coup, as is well known, Chun continued to amass more and more power, leaving Choi in place as a figurehead. By the time Chun declared martial law on May 17 (after he'd had Choi appoint him head of the KCIA in April), Choi was essentially powerless. Kim Yang-woo, of the Kukje Shinmun, in The Kwangju Uprising, described Choi's television address to the people of Kwangju on May 24 (which was only broadcast in Kwangju). He called them "rioters" and urged them to surrender and to throw themselves on the mercy of the martial law authorities. Kim noted that

The broadcast lasted half an hour. During that time the president let his eyes rest on a manuscript in front of him and read the text. He lifted his head to face the camera only three or four times during the whole program.Describing the scene six weeks later, Ambassador Gleysteen wrote that

The precise role Chun played in Choi stepping down is still unknown - another secret Choi "took to the grave". Chun, of course, stepped into the presidency two weeks later:

Choi Gyu-ha (left) at Chun Doo-hwan's (right)

Choi Gyu-ha (left) at Chun Doo-hwan's (right)inauguration as president, Sept 1, 1980 (from here)

From the descriptions of him, Choi sounds like he was picked by Park Chung-hee to be prime minister because he was meant to be a harmless figurehead. A bureaucrat most of his life, he was not prepared for the turmoil that would spread across Korea in the wake of the end of the Yushin system. The people who were prepared to grasp for power in that environment (from Chun to Kim Dae-jung), were all subsequently arrested for (or closely connected to) corruption or embezzlement. It seems that, according to those who observed him during his short presidency, that he was simply wasn't cut out for such a difficult position as he was then put in; he didn't have the power base or connections that others did. He doesn't seem to have been a politician, really. Which is perhaps to say that he wasn't really an asshole, like those who followed him.

Ironically, the date of his funeral will be the 27th anniversary of Park Chung-hee's assassination. From what I've read (though who knows how the media is shaping this), his years since the presidency haven't sounded like those of a man at peace. Hopefully he is now.

Ironically, the date of his funeral will be the 27th anniversary of Park Chung-hee's assassination. From what I've read (though who knows how the media is shaping this), his years since the presidency haven't sounded like those of a man at peace. Hopefully he is now.

No comments:

Post a Comment