Today marks the 43rd anniversary of the beginning of the Gwangju Uprising.

An index of my posts over the years about the uprising can be found here.

I've spent time over the past few years reading through US diplomatic cables from a variety of sources (which appear in this bibliography, which I've just updated). Interestingly, many of the cables which had parts redacted that have been more recently released in unredacted form turn out to have not been censoring material that made the US look bad - they were censoring material that was critical of their ally or that might make prominent Koreans look bad (three of these people became president of the ROK in the 1990s).

The cables actually provide fascinating windows into what was happening in Korea at that time, and I'll post, over the next week, some of the more interesting ones I've found, such as a May 1980 Student manifesto.

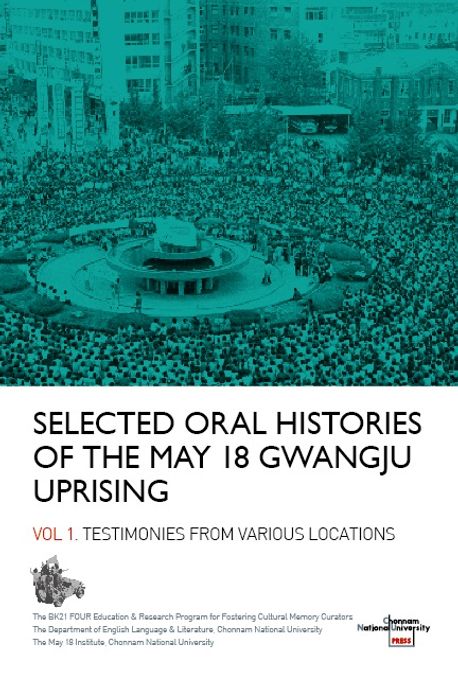

Also worth noting is that a new book has been released:

Kim Yeon-min, Robert Grotjohn, eds, Selected Oral Histories of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising: Vol. 1. Testimonies from Various Locations, Chonnam National University Press, 2023.

The Hankyoreh also reported on disturbing findings by the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission: Martial law forces continued killing Gwangju citizens after suppression operation, says eyewitness

The May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission's chairperson was also recently interviewed by Tim Shorrock, and there is some interesting material there. The chairperson noted that requests have been made to the US for military and CIA documents (State Department and Carter Library documents were released in 2021) and that they may be able to disprove claims by Chun's group, while Shorrock implies they could shed light on the "dark alley that investigators call 'the Fort Benning connection' – that is, the close relationship between Chun and his accomplices with American generals and special forces operatives in Korea." The article does little to shed any light on this, however, merely pointing out a handful of references to American officers who interacted with the ROK military as part of their duties and implying newly-declassified materials may implicate them.

In the aftermath of the “12/12 Incident,” U.S. embassy, military, and State Department officials claimed that Chun [Doo-hwan] was an obscure general little known to US Forces Korea, and said they had been assured at the highest levels it would never happen again. But those claims were untrue, according to James V. Young, who was the military intelligence adviser to U.S. Ambassador William Gleysteen at the time.

Skipping over the fact that Young was the assistant defense attache, the last sentence implies that Young’s revelations (in his 2003 memoir Eye on Korea) reveal that U.S. embassy, military, and State Department officials were lying, whereas Young actually wrote that prior to 12.12, “I began to wonder whether the left hand knew what the right hand was doing—obviously we were in big trouble if Washington had such a superficial understanding of the situation that it did not know who Chun was, especially after all the reporting we had done. The problem was that, while the DIA and CIA obviously had large amounts of information, the State Department, at least at the working levels, was only peripherally aware of this important personality.” [Page 63] Rather than lies, Young points to bureaucracies with differing priorities at work, hence Chun Doo-hwan being "little known" to the State Department.

As well, we're told that

Young wrote that Chun was especially close to Col. Donald Hiebert, a U.S. Army Special Forces soldier who was the U.S. embassy’s defense attache in 1980. Hiebert first met Chun in the 1970s. At that time, “One of [Hiebert’s] frequent associates was a young colonel, Chun Doo Hwan,” Young wrote. “Hiebert had met the colonel in Vietnam, where Chun had commanded a battalion, and had continued their association in Korea. They met rather frequently.” Young said he met Chun for the first time at the U.S. ambassador’s residence in 1972 and several times after that, “usually accompanied by Col. Hiebert.”

The problem with this paragraph is that there's an error in it that renders it pointless: Hiebert was the U.S. embassy’s defense attache in 1972, not 1980. The Vietnam War-era NYT article about the ROK military in Vietnam that is linked to is interesting enough, I suppose, but Hiebert had nothing to do with the events of 1979-1980.

That said, Shorrock is always able to dig up fascinating material, like this interaction between North Koreans and Americans in early June 1980 about the Gwangju Uprising.

Hopefully the US will release the military and CIA records that have been requested, particularly because they provide such an interesting window into that time period; the Embassy cables, for example, feature accounts of meetings with the president, his secretary, military leaders, politicians like Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung, dissidents, and more. I only recently started digging into the FIOA declassified CIA reports, searchable here (though not very conveniently). Some I will post soon, while others, like this one, provide a list of cables (titles, dates, recipients) from 1979-1980 turned over by General Wickham when he retired for declassification review.

Needless to say, there will always be more to uncover about the events of 1979-1980.

No comments:

Post a Comment