Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Sunday, November 13, 2016

Seoul's colonial-era 'Defense-of-the-Nation Shrine'

Korea Expose published an interesting article about the forgotten history of the above set of steps in Haebangchon. Especially interesting was the interview with a local woman who remembers going to the Shinto shrine which used to be at the top of these stairs. The article risks confusing this shrine with another, however.

The actual Gyeongseong [Keijo, or Seoul] Shrine was built on the slopes of Namsan south of what is now Myeongdong Station in 1898; a few stone remains can be seen behind Sungui Women's University. It stood not so far from the original Government General Building (built in 1907 before moving, famously, to the large building that stood behind Gwanghwamun until 1996). Also nearby was the Japanese ambassador's residence (built in 1893, before another was built on what is now Yongsan Garrison in 1909, before the final one was built in 1937 on the location of today's Blue House). Photos of all of these can be seen here.

The more famous Chosen Shrine was built in 1925 and almost became the location of a new national assembly in the early 1960s; it now has an Ahn Jung-geun museum and other monuments to Korean independence fighters. There was also a military-related shrine on what is now Yongsan Garrison (I've never seen any photos of it) as well as other smaller ones throughout the Japanese parts of the city and throughout the country. These did not survive past 1945.

The shrine in the Korea Expose article was the 경성호국신사 (more photos can be seen here). If we follow Norma Field's translation of 호국신사 (in In the Realm of a Dying Emperor: A Portrait of Japan at Century's End), this would be the Gyeongseong Defense-of-the-Nation Shrine. She writes that in 1939 a directive stated that each prefecture in Japan was to have one official such shrine. The souls of dead soldiers were to be enshrined there, and if this sounds familiar, it might be because these were essentially local branches of Yasukuni Shrine. Seoul's was built in 1943, and I'm not sure if Korea had only one such shrine in Seoul, or more than one (though I'd lean towards just one). They would have been used not just for enshrinement of Koreans (who were only being used by the Japanese military in small numbers as volunteers or POW guards up until 1944) but for Japanese who were living in Korea.

At any rate, it would be a shame to see those stairs disappear, which the article states is a possibility. Surely if some of the secondary stairways related to the main shrine on Namsan (now standing near memorials to independence fighters) can be allowed to remain, these can as well.

Monday, September 26, 2016

Dr. Haysmer and the apple thief: The "barbaric American incident" of 1926

Dr. Haysmer and the apple thief: The "barbaric American incident" of 1926

Part 1: Clyde Haysmer, Kim Myeong-seop, and the response in Korea

It's unfortunate that Robert Neff's article in the Korea Times last week has a title that does little to reflect the importance of the story it tells. When it comes to bitter memories of Westerners in Korea, the tale of Dr. Haysmer (erroneously spelled 'Haysmeir' in contemporary news articles) and how, as a missionary, he punished a twelve-year-old boy from stealing apples from the mission orchard stands above the rest. It's best remembered in North Korea, where it became the basis of one its most xenophobic, anti-American, and influential novellas. I first heard of the case by reading Donald Clark's Living Dangerously in Korea: The Western Experience, 1900-1950. I turned up photos related to the story years ago and thought I'd write a quick post including them, but some crowd sourcing of information on Facebook led me to dig further, and I found that the event is far more fascinating than I realized, both for how it was used by different groups for their own agendas at the time, and for how pertinent the story is today.

What follows is based on English-language sources (like the New York Times, Japan Times, Japan Chronicle, North China Herald, Seventh Day Adventist materials and genealogical information from Ancestry.com) and a quick reading of some of the Korean sources (from the Donga Ilbo, Chosun Ilbo, and Maeil Sinbo). A more sustained look at the numerous Korean sources would turn up much more information, as would access to the Seoul Press, which I sadly lack (except for quotations from it in the Chronicle). A number of sources here were provided by Jacco Zwetsloot; they are marked with a ***.

Clyde Albert Haysmer was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on December 6, 1897 to Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) missionaries Albert James Haysmer and Dora Wellman Haysmer, who were originally from Michigan. Dora's father, Elam Van Densen was also an elder in the same church and a missionary. Albert and Dora had started their missionary work in Jamaica in 1893, accompanied by their son, Elam Dolphus, who was seven years older than Clyde. The family would, by 1904, be assigned to Barbados. Both Clyde and his brother would eventually be trained as doctors. An SDA newsletter in 1913 notes under the title "Southern Training School" that "Clyde Haysmer writes from Lowell, Michigan that he is doing work this summer with the Fireside Correspondence School at Washington, D. C." By 1917 his father had become an elder and president of the West Indian Union Conference. In late 1918 his elder brother, Elam, died during the influenza pandemic. Clyde is later found crossing into B.C. in July 1920, two weeks ahead of that year's Alberta Conference Association of Seventh-day Adventists in Calgary, which was announced by his father in the previous month's Advent Review and Sabbath Herald magazine. It was likely here that he met his wife. The July 27, 1979 issue of the Atlantic Union Gleaner described her early life:

Ida Louise Hanson was born to Charles and Helen Hanson at Selbey, South Dakota, on March 4, 1892. The family moved to Alberta and Ida attended school at Lacombe and later at Walla Walla, Washington. She graduated from the nurses course at the Portland, Oregon, Sanitarium in 1920. A year was spent nursing in the Alberta Sanitarium and as school nurse at the Hutchinson Theological Seminary in Minnesota. In 1922 she returned to Alberta and was united in marriage to Dr. C.A. Haysmer.It adds that they spent a year at the Portland Sanitarium. A later issue of Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, from July 9, 1925, announced that on March 20 "Dr. and Mrs. C. A. Haysmer went forward for medical missionary work in Korea. Dr. Haysmer is a graduate of our medical college, and had spent a short time practising at the Portland (Oreg.) Sanitarium, and now takes charge of the Soonan Dispensary in Korea." This was also commented on in the March 31, 1925 issue of Western Canadian Tidings:

It was a pleasure to welcome Dr. and Mrs. C. A. Haysmer in the office for a few minutes Thursday, the 19th. They left for Rest Haven prior to joining the "Empress of Australia" at Victoria on Friday, the 20th. Dr. and Mrs. Haysmer were connected for a number of years with our sanitarium in Alberta and lately with the Portland Sanitarium. They accepted a call to Korea recently and will take charge of the medical dispensary at Seoul. Our prayers go with these faithful workers and others as they leave the shores of the homeland from month to month.They sailed for Korea March 20, 1925, and the May 1925 issue of the SDA publication Far Eastern Division Outlook*** reported that "Dr. and Mrs. C. A. Haysmer are now in attendance at the Language School in Seoul, preparatory to service in the Soonan Hospital Dispensary." As the same magazine*** reported two months later:

Dr. and Mrs. C.A. Haysmer are now in attendance at their second term of language school study in Seoul, Chosen. It is their plan to open the hospital-dispensary at Soonan soon after the beginning of the new year.It would appear that they arrived in Sunan, just north of Pyongyang (and the location of its current airport) earlier than the beginning of the new year, for Korean newspapers would report that his deed which would live in infamy took place that summer. As Robert writes:

During the recent session of the Chosen Union plans were laid for developing as rapidly as possible a strong training center at Soonan for medical missionary evangelists. To this end a nurse's training class will be formed and operated in collaboration with the Chosen Union Training School.

On July 15, while walking through the orchard, he encountered 12-year-old Kim Myoung-sup, a Korean boy living in the neighborhood. Haysmeir later claimed the boy was stealing apples but Korean newspapers reported the boy was merely in the orchard without permission and ran because he was afraid of the American missionary.In his article, Robert lays out some of the differing accounts of what happened. Many accounts say he used silver nitrate on the boy's face(one I found said it was 'silver acetic acid'); this is dealt with in more detail below. What seems clear is that the word 'thief' was still visible on his skin a year later and that he later was forced to leave school. The issue lay dormant for almost a year until the Chosun Ilbo reported on it - extensively - on June 28, 1926; the Donga Ilbo followed two days later, and the incident quickly became a cause célèbre. On July 1 both the Chosun Ilbo and Donga Ilbo referred to the event as the "barbaric American incident." On July 4 the Donga Ilbo published this photo of Kim Myeong-seop; it's hard to make out the scarring:

What followed next was a horrendous act that marred not only the image of missionaries in Korea but also the face of the young boy.

According to Ransford S. Miller, the American Consul-General in Seoul, after Haysmeir caught the boy, he summoned the boy's mother, Yoon, to the orchard. She begged Haysmeir not to summon the Japanese authorities, and he agreed not to but was insistent that the boy had to be taught a lesson. He had one of the nurses bring him some caustic soda (acid) and then used it to write 'dojeok' (thief) on the boy's cheeks. He then proceeded to lecture the boy for over an hour and cautioned the crying boy to never steal again.

As Robert notes,

According to DongA Ilbo, just after midnight on July 1, 1926, Haysmeir went to the boy's house and tried to negotiate a settlement with his mother. She suggested that she would consider the matter closed for a sum of 10,000 yen ($5,000) but Haysmeir refused and countered with an offer of 420 yen as compensation and 200 yen for treatment for a total of 620 yen ($310). Eventually Haysmeir did pay the 620 yen and offered an apology in the newspapers[.]Of course, the newspapers were having a field day. As a Reuters report put it, "A wave of indignation is sweeping Korea." Referring to the Seoul Student Federation, this Donga Ilbo article's headlines give a sense of the outrage being cultivated in Korea by the press:

Student organizations stirred to action...in regard to barbaric American incidentThere were calls for monetary support to treat Kim, who had arrived in Seoul for treatment on July 5. Two days later the Donga Ilbo reported that the Gaesong Youth Federation had met July 5 and that one of its resolutions that day was to send a warning to the “barbaric American, Haysmer.” Within days reports were coming in from around Korea of such actions in places like Mokpo or Masan ("Masan youths roused, excessively aggrieved over the Haysmer incident"). As is described in Donald Clark's Living Dangerously in Korea, "Civic groups joined in. The Bar Association passed a resolution demanding the doctor's deportation. 'We don't like to be experimented on like animals,' wrote a Korean in a letter to the editor of the Seoul Press."

Prepare to send a written appeal to worldwide Seventh-Day Adventist Church

Facts of the insult to the minjok come out: Haysmer threatened the victim's mother, "Pay me 5 won or I'll write 'thief'"

The story told by Kim Myeong-seop [the victim] who arrived in Seoul

Many called for expulsion or legal punishment, and the Japanese authorities soon obliged on the latter request. A handful of articles, originating from Chinese newpapers, suggested that the incident was dug up by the Japanese to encourage anti-American and anti-missionary feeling. For example, the China Weekly Review of August 14 argued that "the Japanese press and police dug up the affair and a great sensation was made of the action of the American missionary in 'lynching' the Korean boy." However, the chronology of newspaper reports suggests otherwise. The first reports in the Korean papers were in late June; the first articles in the Government General-controlled Maeil Sinbo didn't appear until July 4.

Korean groups displayed a great deal of anger, conveyed by the Korean press. One reason that they could express this may be that the "barbaric enemy" in this case was an American rather than a Japanese. In fact, the abstract for a paper (in Korean) titled "Korean National Cooperative Front and Anti-Christian Movements in 1920s - Focused on Haysmer's Event," by Kang, Myung Sook, says of the post-Samil nationalist movement:

To establish a strong movement the Seoul Group made the issue [of] Haysmer's Event in 1926 which happened in 1925. Koreans considered Japanese' brutalities as Haysmer's brutalities. Through the criticizing of Haysmer's Event, Koreans [criticized] Japanese' exploitation and suppression.The idea of this bitter criticism of an American missionary being a surrogate for criticism of Japan has merit, I think. While the Maeil Sinbo would, once it joined in, certainly encourage the Koreans in criticizing American "barbarity," it became apparent that this could also be used against the Japanese. On July 11, the Chosun Ilbo reported that a "second Haysmer incident" had occurred in Masan, where a Japanese person beat a Korean child. On August 27 the Japan Times would report another "second Haysmer case" which took place in Pusan, when a Mrs. Iihara was arrested for pouring coal tar over a Korean girl who stole melons from her orchard. It goes to show how the Korean-owned newspapers would make use of openings given to them by the Japanese authorities.

On July 22, the Japan Chronicle published a statement made to the Japan Advertiser by Baron Atsushi Akaike, a member of the Peers and former Chief of the Metropolitan Police Board, which provided more details on the case:

Unfortunately the report about the branding of the Korean boy 12 years old by a certain Dr. Haysmeir is true. I had hoped with vain hope that it was the usual sort of Japanese newspaper talk, gaining weight in travelling. Plain facts are now before us, so I think it is better to inform the public of the bare truths and let justice have its way than to attempt concealing it and thereby deepening suspicion.A statement regarding the investigation's findings by SDA Mission superintendent Edward J. Urhquart appeared days later in (most likely) the Japan Advertiser, which was then quoted in part by the Japan Times on July 23:

"The facts are simple. Kim En Sop, the young boy, stole a few apples and was caught by Dr. Haysmeir, chief of the local hospital and missionary. Dr. Haysmeir sent for his mother. When she arrived he demanded a damage of Y5 a sum impossibly large for her means. When it was manifest that she could not pay it, he instructed the nurse to bring shosangin [초산은 ] (translated in Japanese-English Dictionary as nitrate of silver, caustic silver or lunar caustic) and wrote the inscription on the boy's face. Accused, thereupon, wrote the syllables in to eunman on the left cheek of the boy with nitrate of silver and the latter chyok on the right cheek, and baked the syllables in the sun for about half an hour before the boy was allowed to go home. The doctor also told the boy to come and weed the grass in his garden for a week in lieu of payment of damage, but the boy never returned.

The drug used for the inscription has since corroded part of the outer layer of Kim's cheek, and though he was cured of the injury in four or five days, pigmentary deposit of blood due to inflammatory hyperemia still remains on the outer layer of the skin. It is expected that proper medical treatment of some six months' duration will be required to remove the traces. As to the reason why the affair, which took place last September, had not come to the notice of the local police until recently, Mr. Akai, Chief Public Procurator in Heijo Local Court, is represented as stating in a press interview that Kim, from remorse at his own misdeed, had kept it secret, and that the discovery was due to his having been brought to a hospital for treatment by Min (mentioned in the writ of indictment) who met Kim at the market on the 11th of the Fifth Moon and saw the disgraceful marks on his cheeks.

The mother was told that this time something must be done by way of teaching the boy the seriousness of his offence. Whereupon the doctor made the mother two propositions: (A) That the mother pay two yen and have written on the boy's face with silver nitrate two Korean characters meaning 'thief,' or (B) That this boy be taken to the police station. (It was explained to the mother that the marks from the silver nitrate would be carried for about two weeks.)The Seventh Day Adventists' General Conference Committee Minutes for 1926 reveal in more detail how the General Conference Committee responded to these events on July 14, 1926:

The mother, hearing this proposition, of her own volition chose the mark of thief on the boy's face rather than a visit to the police station. The doctor, therefore, wrote the two characters upon the boy's face and he was liberated. (Now I wish to make it plain that there was no attempt at torture, nor was the boy driven to tears at any time during the proceedings. The act was done at the request of the mother, in preference, of course, to a visit to the police.)

Special meeting was called to give consideration to an Associated Press report, stating that one of our doctors in Korea had branded the word "thief" on the face of a Korean boy caught stealing apples from the mission yard.A few hours later, they got a response:

Not having any information other than that contained in the newspapers, it was decided to request J L Shaw to call at the State Department in Washington, to ascertain whether the matter had been reported to them.

KOREAN INCIDENT:Regarding the suggested public statement, on July 16 the Japan Times reported that the Foreign Mission Board of the Seventh Day Adventists was investigating the case, and that the board's chairman stated that the Board "disapproves and dissociates itself utterly from any mistreatment of any person by any missionary." Two days later, on July 16, the matter was brought up again by the General Conference Committee:

J L Shaw reported the result of his visit to the State Department. The Department had not received a report on the branding of the Korean boy, but on request of Elder Shaw at once cabled for information.

After some study as to what should be done, it was decided to ask I H Evans to cable Korea, to ascertain facts relative to the charges against Dr Haysmer referred to in the newspapers.

Further, that the chairman be asked to issue a statement to the Associated Press to the effect that we utterly repudiate any mistreatment of any race by a missionary, and that we only await confirmation by the State Department of the reports, and our own official channels, before taking action in the matter.

Adjourned.

W A SPICER, Chairman.

B E BEDDOE, Secretary.

KOREAN INCIDENT:On July 18 it was reported that Haysmer had been "dismissed from the denomination." He was not kicked out of the SDA; rather, he had been stripped of his position as a missionary. The July 29, 1926 issue of the SDA's Advent Review and Sabbath Herald contains this report about the incident by General Conference Committee chairman W.A. Spicer; you can see how some of the information was edited for public consumption:

Report was received from the Department of State relative to the situation in Korea, as follows:

"Reply received from the American Embassy, Tokyo, to request through the Department of State of the General Conference, Seventh-day Adventists, Takoma Park, concerning the alleged branding of a Korean boy by Dr Haysmer, missionary at Chosen:

"'According to a statement which was issued by the Governor General at Chosen, Korea, which has been substantially confirmed by the president of the Mission Board as received on July 15, from Miller, Dr. Haysmer last September branded the word "thief" with chloric acid which was said to have been silver nitrate according to the mission superintendent. The markings failed to disappear, as was expected. There followed agitation, started by Koreans and Japanese, after a solatium was given to the family of the boy. Proceedings against Dr Haysmer were instituted on July 12, according to the American Embassy."

Also the following cable was received from E J Urquhart, the superintendent of the Chosen Mission:

"July 15,1926 Heinanjunan.

“Adventist, Evans.

" Newspaper reports exaggerated. Public opinion adverse. Trial soon. Following Shanghai advice, Haysmer dismissed. Outcome uncertain."

In view of this word received by cable, stating that the missionary in Korea who had marked the word "thief" on the face of a Korean boy has, on the advice of the Far Eastern Division, been dismissed, it was--

VOTED, That we approve of the prompt action taken by our board in the Far East in dismissing the missionary.

Adjourned.

W A SPICER, Chairman.

B E BEDDOE, Secretary.

SAD NEWS FROM KOREAThe August 4, 1926 issue of the Atlantic Union Gleaner offered this commentary on Haysmer and his dismissal:

WHEN newspaper dispatches reported the marking of a Korean schoolboy's face by one of our missionaries as a punishment for stealing, many wrote us for information. Our people, naturally, hoped for denial of the report. Such have doubtless seen in the press our statements, first of disapproval and repudiation of any mistreatment of any one by a missionary, and later the announcement that our Far Eastern Division committee had taken action.

On seeing the press reports, we felt assurance that the division office in Shanghai would take steps to ascertain the facts and act in the matter. As given out by us a week ago to the press, the following Cable was received in Washington from Elder E. J. Urquhart, of the Korean Union:

"Following Shanghai advice, Haysmer dismissed. Trial soon. Outcome uncertain." On receipt of the cable, our board in Washington took action, voting, "That we approve of the prompt action taken by our board in the Far East in dismissing the missionary."

Meantime the State Department in Washington had been making inquiry at our request, their information confirming the fact that the doctor had marked the boy's face with a solution, "said by the mission superintendent to have been silver nitrate." We learn also that when, "contrary to expectations, markings did not disappear," the doctor paid a monetary consideration to the boy's family. We know from the press dispatches that he also advertised his apologies in the Korean press. But the act of a thoughtless moment could not be recalled. Though the missionary would gladly have spent his life in ministry to the sick and needy in that hospital dispensary, some other must do this service. We hope a man may quickly be found to fill the gap in this emergency. The Far East committee is no doubt already making call to this end.

We may well be thankful that in every great mission division we have these division conference committees, made up of responsible and experienced men, ready on the ground to give counsel and to act in every emergency.

W. A. SPICER,

President General Conference.

ENCOURAGING EDITORIALFor Haysmer, being dismissed was likely the least of his problems. The New York Times reported that on July 13 that he had been "formally charged with inflicting bodily injury by the Heijo [Pyongyang] Procurator General." His trial was to take place at the end of that month in Pyongyang, though luckily for the doctor, as Baron Akaike, revealed, "It is telephoned from Heijo that Dr. Haysmeir will not be held in custody pending trial of the case."

The members in our field will take courage from the following editorial copied from the Spokane "Chronicle".

Cruelty is not Religion

"The Seventh-day Adventist church should have commendation of every denomination maintaining missions abroad for its dismissal of the missionary charged with branding the cheeks of a Korean boy for stealing apples.

"Missionaries in the foreign fields are supposed to typify American ideals of religion. A single act such as that charged against the discharged missionary misrepresents America in foreign countries and discounts the sincere efforts of all missionaries.

News Item Copied from same Paper

"Branding Cost Him Job"

"Washington, July 17 (A. P.)— Dr. C. A. Haysmer, the Seventhday Adventist missionary charged with branding the cheeks of the Korean boy for stealing apples, has been dismissed by the Far Eastern organization of the denomination, Adventist headquarters here announced today. The mission board here approved the dismissal."

While every Seventh-day Adventist blushes with shame when he thinks of the foolish mistake of Dr. C. A. Haysmer, yet we must not let this episode deter us from courageously meeting the public and asking them to support our foreign missions program.

No reasonable man will cast reflections on the integrity and honesty of the denomination because one of its 9000 workers committed an unpardonable crime. We can yet turn this dark experience into a mighty victory for our Harvest Ingathering work by assuring our friends that the high standards of our denomination do not countenance cruelty or oppression of any kind, and the prompt dismissal of Dr. C. A. Haysmer testifies to that fact.

F. D. Wells.

The trial began July 29 and much was made of his court appearance in Pyongyang. The Donga Ilbo published this photo of Haysmer:

The Maeil Sinbo published this photo of him in court:

A slightly clearer version is here***:

The Japan Chronicle reported on the trial:

PROCEEDINGS IN PUBLIC COURT.A Japan Chronicle report describes the outcome of the trial:

The Seoul Press produces a long account of the proceedings at Heijo Local Court on the 29th ult. when Dr. C. A. Haysmeir appeared to answer a charge of inflicting bodily injury on a Korean boy. Mr. Justice Aramaki presided and Mr. Mitsui, for the defence. Long before the court was opened at 9 a.m. large numbers of Koreans, despite the wet weather, assembled at the gate, all eager to get admission tickets, which were restricted to 100 owing to the limited accommodation. Dr. Haysmeir appeared in lounge suit.

After all usual preliminaries were gone through, Public Procurator Shimmnaru explained why action was brought against the doctor, and examination of him by the Court followed with English interpretation by Mr. N. Kondo. The accused admitted the facts set forth in the speech of the Public Procurator, and expressed his regret that the inscription on Kim's cheeks had not yet vanished now that nearly one year had elapsed since he wrote the syllables meaning thief with nitrate of silver with the intention of chastising the youthful delinquent, and thinking that the inscription would disappear in a fortnight or so. In answer to a question by the Court the accused also stated that were apples stolen so frequently as was done by the Korean boy he would have punished an American boy in the same way.

The Public Procurator then delivered another speech in the course of which he said that as the accused admitted the charge his offence was quite evident. A question in doubt, however, was that the accused wrote the syllables to chyok on the Korean boy's cheeks really believing that they would vanish in a fortnight. At any rate, the act of the accused was cruel and repulsive, especially when the fact was taken into consideration that he was a medical missionary of the religion propagating the text of universal love. It would be no very great exaggeration to say that by making such an ignominious inscription on the cheeks of the Korean boy, the accused morally killed him, and for his act deserved severe punishment. At the same time the Public Procurator acknowledged that the bodily injury caused by the act was not serious and brought home the fact that the accused was now penitent, having paid damages to the victim. The majesty of law, however, must be upheld, and the Procurator asked the Court to sentence the accused to three months' penal servitude by virtue of Art. 204 of the Penal Code.

Mr. Mitsui, counsel for the defence, pointed out that the crime of bodily injury presupposed an unlawful attack, but in the present case the accused acted after obtaining the consent of the mother of the boy, so that the act of his client did not constitute the crime of bodily injury. Could his act be well termed violence, then it required a suit by the party concerned for the Court to take it up - a thing omitted by the party interested. Mr. Mitsui insisted on the acquittal of his client as not guilty. The Court reserved judgment till August 5th.

Judgement was delivered on Dr. Haysmeir, in the Pyongyang District Court, Korea, on the morning of the 5th instant, when he was sentenced to three months imprisonment with postponement of execution of sentence for two years. Dr. Haysmeir is reported in a Japanese dispatch to have shown relief at this sentence.On August 7, the Maeil Sinbo reported that the prosecution considered the fact that the sentence was suspended to be unfair and filed an appeal, meaning that Dr. Haysmer's ordeal was not yet over. On August 26, the Chronicle reported that "The Procurator's appeal in the Haysmeir case is to be heard by the Heijo [Pyongyang] Court of Cassation on the 26th" of August. The Maeil Sinbo later reported that on September 2 the Pyongyang Court of Cassation gave him the same result as the first trial – "two months in prison [sic] suspended for two years." This was declared by the prosecution to be unfair and immediately appealed yet again, meaning the next trial would be in Seoul. The Maeil Sinbo was nice enough to include a photo with this report - said to be of the apple tree in question, with Haysmer's house behind:

Meanwhile, the summary of the SDA's General Conference Committee meeting of October 14, 1925 makes clearer why the General Conference Committee dismissed him:

DR C A HAYSMER:Meanwhile, the Maeil Sinbo reported that the appeal, held at the high court in Seoul, began on November 5, and was dismissed on November 18. As the Chronicle reported,

A petition had been received from a number of brethren in Korea, requesting that Dr. C A Haysmer be allowed to remain in the Korean field. The situation was carefully reviewed, and it was—

VOTED, That answer be sent to the dispensary workers at Soonan expressing our appreciation of their sentiments so kindly expressed, but replying that in view of the unfortunate incident and the world-wide publicity given to it, and the possibility that agitators at any time might easily make use of the case to promote their own ends and to oppose the cause of missions, we feel that the best interests of our brother and the best interests of the cause in general will be served by retirement now from the field.

HAYSMEIR CASE. PROCURATOR'S APPEAL DISMISSED.On November 26 the Donga Ilbo reported that Haysmer would leave Korea within a week. He and his wife appear on the passenger list for the Protesilaus, which had sailed from Yokohama and arrived in Vancouver December 22, 1926. It notes that he had $150 with him and that his passage was paid by "Korea Union Mission, SDA." A later SDA publication shows that "Prof. and Mrs. A. R. Tucker, of Washington, [went] to Korea" in August of 1927 - perhaps they replaced him.

In the Seoul High Court of Justice Judgement was delivered on Mr. Hays- Their, the American missionary doctor, of Junan, Heian- nando, Korea, yesterday morning at 11 o'clock. The procuratorial appeal was dismissed, and Dr. Haysmeir was sentenced to three months Penal servitude with postponement of the sentence for two years, the same as in Courts of First and Second Instance. This judgement is final.

Ida Haysmer's obituary in the July 27, 1979 issue of the Atlantic Union Gleaner described her life after her marriage to Clyde Haysmer:

Later, after spending a year at the Portland Sanitarium and a short term in the mission field, they connected with the New England Sanitarium and Hospital in Stoneham, Massachusetts, in 1927. Except for three interludes during which Dr. Haysmer took further surgical training, they were connected with that institution until 1964. During much of this time Mrs. Haysmer served in various nursing capacities.If this narrative seemed to gloss over their time in Korea, describing it as only "a short term in the mission field," it may be because the obituary was written by Clyde Haysmer himself. This omission may give a hint as to his feelings about the incident half a century later. His appearances on passenger lists traveling to and from England in the late 1920s and late 1930s may point to the "interludes" when he undertook "further surgical training." Four years after writing this obituary, he died in Alabama in November 1983.

After a year of travel, Yucca Valley, California, was chosen as the best location, both for climate and to carry on surgical practice. Owing to their increasing years, it was thought best to be near relatives; so in 1977 a move was made to Alhambra, California, to be near their niece and nephew.

Mrs. Haysmer's health deteriorated and she died in the White Memorial Hospital at 7:00 a.m. October 28, 1978. A memorial service was held in Yucca Valley and interment was in the family plot in Stoneham, Massachusetts.

While this would appear to be the end of the story, it went well beyond Korea, and in the summer and fall of 1926, as legal action was taken against Dr. Haysmer, Japanese-controlled newspapers and foreign-run newspapers would battle over interpretations of the incident, as we will see in part two.

Labels:

Books,

Colonial Era,

Foreigners,

Japan,

Media,

Medical Issues

Friday, August 19, 2016

Comfort Women, nationalism, and the inculcation of anti-Japanese feeling

[Note: There are some disturbing images below.]

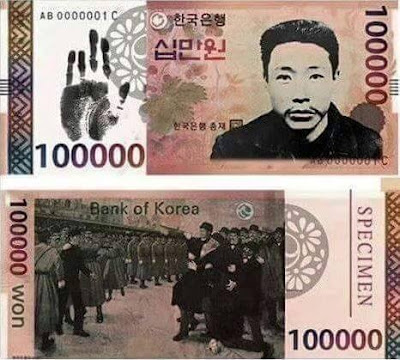

The image above was posted on Facebook along with a message in Korean asking for support for this to be the new 100,000 won bill; it received 31,000 likes last I looked at it (awhile ago now, admittedly). For me, the movie title 'How to lose friends and alienate people' comes to mind. Well, it's not the first time a "ruthless political terrorist" has been suggested for the 100,000 won bill (the difference being that the above An Jung-geun bill hasn't been officially suggested). Should something like this come to pass, however, it would be amusing if Japan issued a bill with Hideyoshi Toyotomi and the 'ear mound' that stands in Kyoto on it.

On a similar topic was this column by 'foolsdie' in the Korea Times, titled 'Are we still allies?' which complained about Donald Trump's comments on the US-ROK alliance before turning in another direction:

Michael Breen touched on the topic of Korea-Japan relations when he wondered if the comfort woman statue in front of the Japanese Embassy should be moved to the exit of Gangnam Station near where a woman was murdered because of her gender in May by a man who had been rejected by women. (Of course, he was mentally ill. It's interesting how when someone commits a crime that could be construed as sexist or racist (like murdering a foreign English teacher or a military doctor) they're often described as 'mentally unstable' or 'deranged'.) Breen describes

In the spring of 2014 I visited the Museum of Korean Modern Literature in Incheon and came across a large exhibit on the first floor about the comfort women. There were many comic books presented with each page as a poster affixed in order along the walls. One, below, was titled '70-year-long nightmare':

As always (as I've noted before regarding films here, and here, and here) it all begins with an overly simplistic tale of happy-go-lucky innocent children picking flowers (hell, even Peppermint Candy 'begins' this way) before history (or an evil invader) bowls them over.

Another was titled "Where are we going?" - I've posted a few pages below:

One has to admire the design of this work, though I couldn't help starting to feel that perhaps the artists were depicting the women's suffering a little too enthusiastically. And then I saw this comic:

What follows (I chose not to photograph it) is an incredibly graphic depiction of the rape of a child. That she was a child was made clear by the size of her breasts and lack of pubic hair - it was actually that graphic - and I was appalled that something like that was on display for people of all ages to view at the museum. That said, I wasn't particularly surprised by it, considering the apparent approval there is for such depictions of suffering, as well as the lack of concern there has been regarding raising the low age of consent in Korea. It also brought to mind this photo (of a foreign woman) posted in public as a photo contest entry at the Boryeong Mud Festival in 2011, at least in terms of female nudity being thoughtlessly allowed in a public forum. Also worth remembering is a blog post by Oranckay back in 2004 when the Korean government went out of its way to block its citizens from seeing videos of the beheading of Kim Sun-il in Iraq. In that post he referenced a Korean feminist website (perhaps Ilda) which criticized the government for trying to hide images of the death of a Korean male from the citizenry while letting images of the bodies of prostitute Yun Geum-i (killed by a G.I. in 1992) and the two girls run over by a U.S. bridge-layer (in 2002) proliferate without comment. These images were used to mobilize resistance to the U.S. presence in Korea, and in thinking of this - and of depictions of the comfort women - I'm reminded of a passage in Sheila Miyoshi Jager's 2003 book Narratives of Nation Building in Korea : A Genealogy of Patriotism which, while it refers to anti-USFK campaigns, is also applicable in some ways to the comfort women issue (and is very applicable to Anti-English Spectrum):

The torture of Yu Gwan-sun by Japanese police;

The suppression of the Samil protests by Japanese police;

The assassination of D.W. Stevens in 1908;

The assassination of Ito Hirobumi in 1909;

Also included was Yun Bong-gil's bomb attack in Shanghai in 1932. What we see there, of course, is that the (passive) women serve as victims to motivate the (active) men to carry out acts ofterrorism justifiable revenge. Likewise, images like these posted in a public space seem to promote or justify a continued antipathy towards Japan:

Having been reading about Canada's participation in World War I lately (in Marching As to War: Canada's Turbulent Years, 1899-1953 by Pierre Berton) I couldn't help but remember the final stanza of "In Flanders Fields":

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

As is noted in the poem's Wikipedia entry,

The image above was posted on Facebook along with a message in Korean asking for support for this to be the new 100,000 won bill; it received 31,000 likes last I looked at it (awhile ago now, admittedly). For me, the movie title 'How to lose friends and alienate people' comes to mind. Well, it's not the first time a "ruthless political terrorist" has been suggested for the 100,000 won bill (the difference being that the above An Jung-geun bill hasn't been officially suggested). Should something like this come to pass, however, it would be amusing if Japan issued a bill with Hideyoshi Toyotomi and the 'ear mound' that stands in Kyoto on it.

On a similar topic was this column by 'foolsdie' in the Korea Times, titled 'Are we still allies?' which complained about Donald Trump's comments on the US-ROK alliance before turning in another direction:

Then, Obama's recent visit to Hiroshima acted as a wedge. It's laudable for him to try to free the world of the fetters of nuclear weapons. But here, memories of Japan's brutal occupation remain fresh even after the passage of 70 years. Obama was perhaps too engrossed in the heat of the moment to say out loud that the nuclear attacks were the result of Japan's aggression and those killed and maimed were the victims of its failed leadership. Ironically, his visit has freed ultranationalist Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his ilk from the atrocities it had committed. Human rights are one of two pillars of U.S. foreign policy, with nonproliferation being the other. For sure, Obama's visit didn't help much on human rights.Regarding "memories of Japan's brutal occupation remain fresh even after the passage of 70 years" (and I wonder why that is?), perhaps it's worth noting that most countries don't dedicate their education system and media to instilling historical bitterness quite like the Koreas, and thus not everyone believes that any given Japan-related news item is an occasion to dredge up memories of suffering. But I'll concede that it's a great way to keep people's minds off more important things. The Korean government itself apparently had no such complaints; a foreign ministry official said, "In such a historic speech, it is meaningful that he clearly mentioned Koreans, putting them on par with American and Japanese victims." Which might suggest that confirming victim status is a diplomatic victory. The problem is that it seems like aspiring to victim status is part of the Korean national identity, and thus there are some who would insist that Koreans' suffering should be elevated above everyone else's.

Michael Breen touched on the topic of Korea-Japan relations when he wondered if the comfort woman statue in front of the Japanese Embassy should be moved to the exit of Gangnam Station near where a woman was murdered because of her gender in May by a man who had been rejected by women. (Of course, he was mentally ill. It's interesting how when someone commits a crime that could be construed as sexist or racist (like murdering a foreign English teacher or a military doctor) they're often described as 'mentally unstable' or 'deranged'.) Breen describes

an interview with a prominent expert on prostitution. When I asked what she thought of the comfort women issue, she asked me to put my pen down so that she could rant politically incorrectly off-the-record.In a Korea Times column, Maija Rhee Devine (who will give a lecture for the RAS in September on the comfort women) asks "Are comfort women lying?" Her ultimate answer is no, but she points to criticism of the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, who are suspected of having "coached" the comfort women in some of their testimony.

"It's a joke," she said. "Pure hypocrisy."

We all know Japan was guilty of terrible things up to 1945, but, she said, this chauvinistic focus on justice for a historical matter is popular with Koreans because it conveniently distracts us from the real issue and our own continued guilt.

The real issue is the attitude in Korea of men towards women and human trafficking in the sex industry that operates on the scale it does as a consequence of that attitude.

That explained for me the odd fact that the comfort women story did not surface until 40 years after the war. People in 1945 were of course angry about the Japanese occupation but the comfort women did not appear important then, few even knew about it because male attitudes toward women and the trafficking of young women to service them hadn't changed with national liberation.

In the spring of 2014 I visited the Museum of Korean Modern Literature in Incheon and came across a large exhibit on the first floor about the comfort women. There were many comic books presented with each page as a poster affixed in order along the walls. One, below, was titled '70-year-long nightmare':

As always (as I've noted before regarding films here, and here, and here) it all begins with an overly simplistic tale of happy-go-lucky innocent children picking flowers (hell, even Peppermint Candy 'begins' this way) before history (or an evil invader) bowls them over.

Another was titled "Where are we going?" - I've posted a few pages below:

One has to admire the design of this work, though I couldn't help starting to feel that perhaps the artists were depicting the women's suffering a little too enthusiastically. And then I saw this comic:

What follows (I chose not to photograph it) is an incredibly graphic depiction of the rape of a child. That she was a child was made clear by the size of her breasts and lack of pubic hair - it was actually that graphic - and I was appalled that something like that was on display for people of all ages to view at the museum. That said, I wasn't particularly surprised by it, considering the apparent approval there is for such depictions of suffering, as well as the lack of concern there has been regarding raising the low age of consent in Korea. It also brought to mind this photo (of a foreign woman) posted in public as a photo contest entry at the Boryeong Mud Festival in 2011, at least in terms of female nudity being thoughtlessly allowed in a public forum. Also worth remembering is a blog post by Oranckay back in 2004 when the Korean government went out of its way to block its citizens from seeing videos of the beheading of Kim Sun-il in Iraq. In that post he referenced a Korean feminist website (perhaps Ilda) which criticized the government for trying to hide images of the death of a Korean male from the citizenry while letting images of the bodies of prostitute Yun Geum-i (killed by a G.I. in 1992) and the two girls run over by a U.S. bridge-layer (in 2002) proliferate without comment. These images were used to mobilize resistance to the U.S. presence in Korea, and in thinking of this - and of depictions of the comfort women - I'm reminded of a passage in Sheila Miyoshi Jager's 2003 book Narratives of Nation Building in Korea : A Genealogy of Patriotism which, while it refers to anti-USFK campaigns, is also applicable in some ways to the comfort women issue (and is very applicable to Anti-English Spectrum):

Like Sin [Ch'ae-ho], chuch'eron [the (supposedly) North Korean-influenced anti-imperialist 'philosophy' of leftist South Korean students popular from the mid-1980s to the 1990s] sees the entire history of the Korean people as an epic struggle to overcome foreign domination and feudal oppression. The historian's task, in other words, entails the examination of the experience and legacy of the Korean people's struggle to preserve their "core" identity. [...] Perceived as a significant threat to this core identity, miscegenation became associated with a whole host of related themes about the defense of the social body - the retrieval of a superior "core" Korean identity in the name of a phantasmic Korean essence. The ability of the foreign male to penetrate (literally) the inner and inviolable sanctum of Korean women and to establish conjugal alliances with them was perceived not only as a threat to the viability of the family, but as an act that undermined the fundamental cohesion and identity of the Korean nation. Thus we find in Korea that those women who formed marriage alliances across racial lines were popularly perceived as being women of "loose" morals: prostitutes, bar hostesses, or entertainers. In fact the were represented as the polemical inversion of the idealized virtuous female associated with Korea's traditional romance narratives. By allowing themselves to be appropriated by the West, these women were simultaneously perceived as being victims of Western imperialism and faithless profiteers of American capitalism. Both pitied and despised, the whore thus became the symbol of the nation's shame as well as the rallying point for national resistance. (Pages 71-72)

One can't help but notice the role women other than the comfort women play in depictions of the colonial era. Years ago I posted excerpts of children's books depicting the colonial era, which depict certain events the publishers thought were important, such as the murder of Queen Min by Japanese assassins;

The torture of Yu Gwan-sun by Japanese police;

The suppression of the Samil protests by Japanese police;

The assassination of D.W. Stevens in 1908;

The assassination of Ito Hirobumi in 1909;

Also included was Yun Bong-gil's bomb attack in Shanghai in 1932. What we see there, of course, is that the (passive) women serve as victims to motivate the (active) men to carry out acts of

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

As is noted in the poem's Wikipedia entry,

[Paul] Fussell criticized the poem in his work The Great War and Modern Memory (1975). He noted the distinction between the pastoral tone of the first nine lines and the "recruiting-poster rhetoric" of the third stanza. Describing it as "vicious" and "stupid", Fussell called the final lines a "propaganda argument against a negotiated peace".Is the propagation of such images as those above (especially in a manner meant to communicate to the young) not, in its own way, similar propaganda? This is not to say Korea is the only side at fault, of course - political realities in both Japan and Korea militate against solving the Comfort Women and Dokdo issues, and Japan's apologies (listed here - to 2005 - by Konrad Lawson) have often fell short of the mark (though a cultural tendency towards indirectness plays a part in this). Another elephant in the room is the effect on Japanese attitudes towards the war of the U.S. occupation of Japan and the American decision to preserve the imperial institution and protect the Emperor from prosecution during the Tokyo trials; as John Dower has put it, if the Emperor, in whose name the war was fought, wasn't going to be held responsible, why should anyone else feel guilty? One can only hope that, much like an ascendant Germany pushed the UK and France into an alliance before WWI, China's rise will have a similar effect at some point in the future. But as long as the Korean Gordian Knot - its division - remains in place, other problems related to mid-20th century history will be difficult to solve. An insistence in Korea on allowing displays (and popular culture) to portray Korea as a historical victim to inculcate historical bitterness in order to distract the populace and/or encourage a nationalist belief in Korea's moral superiority strikes me as something that will be counterproductive in the long run - even if it has its uses in the short term.

Labels:

Colonial Era,

Education,

Japan,

RASKB,

Xenophobia or Nationalism

Monday, April 11, 2016

Interview with The Korea File on WW2 POWs in Colonial Seoul

Last year I posted links to an interview Andre Goulet did with me for his podcast, The Korea File (Part 1: "A History of Korean Social Movements," Part 2: "Korean Identity and Anti-Americanism," Part 3: "Weed, Counterculture and Dictatorship") and a few weeks ago he posted a the final part, "Prisoners and Propaganda: WW2 POWs in Colonial Seoul."

Thanks again to Andre inviting me to do this interview; have a look under "Episodes" here to look through the other interviews about Korean music, culture, and society he's done.

More about the WWII allied POWs in Korea can be found here.

Thanks again to Andre inviting me to do this interview; have a look under "Episodes" here to look through the other interviews about Korean music, culture, and society he's done.

More about the WWII allied POWs in Korea can be found here.

Monday, March 14, 2016

White Day!

Men check out the candy selection at L Dept. Store on White Day, 1993 (from here).

Today is White Day (well, it's the 14th in the US), and I was made to think of it during a presentation in which a classmate spoke on this post about Valentine's Day and White Day's origins (note that it gives only the origin of the former; one assumes the author didn't want to draw attention to the Japanese origin of the latter). Also mentioned in the presentation was the list (similar to this one) of "__days" which occur on the 14th of each month in Korea, though I don't think anything beyond white and black day exists outside of such internet posts.

The first mention of White Day that turns up in the Naver News Library is this Hankyoreh editorial from February 14, 1989, titled "Behind chocolate hides a cunning business ploy," which concludes by saying that companies conjuring up White Day to make kids pay twice is improper.

It's mentioned twice in 1991 in a column the Maeil Gyeongje published written by people describing their married life. This one describes how the writer's husband forgot her birthday and said he'd celebrate it on the lunar calendar, and seemed to forget again but eventually surprised her with roses. She notes that he always gave her presents before that, even on "white day, a day he criticized as one made by merchants in order to sell candy."

The most interesting reference I found in 1991 was this one in the Kyunghyang Shinmun on March 11 titled "日(일),야광女子(여자)속옷판매 화이트데이 선물용: [In] Japan, glow-in-the-dark women's underwear sold as white day present." As the article puts it, "For the coming 14th (white day), a women's underwear company in Japan plans to sell 400,000 pairs of glow-in-the-dark panties to Japanese men wanting a present that their lover will never forget."

New word for the day: 야광 - glow in the dark.

Monday, March 02, 2015

Lawmaker criticizes textbooks for correctly describing the violence of the Samil protests

An article in today's Joongang Daily declares in its headline that "Textbooks do disservice to March 1 movement."

In a lengthy recounting of a violent protest in Sacheon, Pyeongannam-do on March 4, which Baldwin describes as a "typical demonstration that began peacefully and ended in violence," three Korean police officers are reported as being killed in addition to a Japanese police officer, which makes clear that the numbers above do not include Korean Government General employees, suggesting that more people died than are listed. Most ironic in the assertion that the Samil Protests were peaceful is this statement by Baldwin:

The tale of "peaceful Samil demonstrations" serves the cause of depicting Koreans as a peaceful people beset upon by marauding outsiders; that is to say, victims with no responsibility for their actions. What better way to depict this fairy tale than a children's book about Yu Gwan-sun from the 한국 위인 전집 (Great people of Korea Collection) published by 노벨과 개미(looked at in more detail here):

Evil Japanese:

Peaceful, victimized Koreans:

Returning to the Joongang Daily article:

Can you imagine any of the male icons of the Korean independence movement being depicted in this way? Besides being the oddly cheerful face of the fight for independence, she's often depicted as the embodiment of victimization (and thus embodies Korea throughout its entire history, according to some nationalist takes on Korean history). Here she is in the 'Great people of Korea Collection' book about her:

She also helps sell chicken, apparently (from 2005):

The final paragraph of the Joongang Daily article offers this short biography of Yu:

Rep. Han Sun-kyo, a lawmaker of the ruling Saenuri Party, told the JoongAng Ilbo on Thursday that he analyzed Korean and Japanese history textbooks he received from the Seoul-based think tank Northeast Asian History Foundation and Korea’s Ministry of Education and found the results troubling.The problem is, the textbooks describing the independence movement as being "violent" are being accurate. While some of the Japanese dispatches during the Samil Uprising reported in the New York Times described violence on the part of demonstrators, I didn't realize just how violent the protests were until I read Frank Baldwin's "Participatory Anti-Imperalism:The 1919 Independence Movement" (Journal of Korean Studies, Volume 1, 1979, pp. 123-162). One assumes this contains some of the material in his dissertation, "The March First Movement: Korean Challenge, Japanese Response" (Columbia University, 1969). In his article, he notes that between March 1 and April 10, 1919, there were "approximately 667 peaceful demonstrations" as compared with "approximately 460 violent incidents." Here is his description of the nature of the protests:

He said a “considerable number of Japanese history textbooks are distorting the facts or minimizing the significance of the March 1 Independence Movement.”

March 1, 1919, remains a touchstone of Korean nationalism as the day when activists declared Korea’s independence and triggered large-scale peaceful demonstrations against Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945).

One Japanese middle school history textbook published by Jiyusa says the March 1 independence movement in Seoul “initially was planned as a non-violent rally but gradually became a large-scale movement,” and that “the army was mobilized and because of a clash on both sides, there were many casualties.” [...]

But Han added that Korean history textbooks also have inaccuracies, and there are many cases where they “describe the non-violent March 1 movement as violent” or do not mention key events or figures such as Yoo Gwan-soon’s martyrdom. [...]

According to Han’s study, half of the eight Korean high school history textbooks inaccurately described the independence movement as being “violent.” Three other textbooks failed to describe the movement adequately.

He found that only one publisher, Chunjae Education, explained the movement accurately and in detail. “As time passed, the protests grew more intense and military and police fired at people during the demonstrations, leading to deaths,” it said. The text emphasized, “The demonstrations were highly regarded internationally for holding to the principle of non-violence while trying to express resistance to Japanese imperialism.”

Initially the demonstrations were nonviolent, partly to enhance the moral appeal of the protest and partly because of the vastly superior Japanese police and army forces. The usual pattern of demonstrations was that activists assembled a crowd and a local leader read the declaration of independence. The crowd roared its approval and then marched around the area shouting for Korean liberty.Before those additional troops arrived, however, the Government General was hard pressed to maintain control and protect its staff, settlers, and infrastructure:

As the independence movement spread and intensified, however, its character changed into often violent confrontation. This was a response to the severe, frequently brutal suppression of the protest by the Government General, which included firing on unarmed crowds and torture of prisoners. In many areas, a peaceful demonstration was suppressed by the authorities with force, and resulted in violent counterattacks on police and gendarmes. In other areas, frustrations, anger, and pent-up grievances turned peaceful demonstrations violent even without official provocation. In still other cases, tension from sustained demonstrations and confrontations, probably exacerbated by official violence, erupted into assaults on Government General personnel and facilities. In late March and early April, parts of Korea were in open, bloody rebellion. Governor General Hasegawa Yoshimichi requested troop reinforcements

During March and April the first stage of the 1919 movement occurred—the overt and violent period. Hundreds of thousands of Koreans engaged in open political actions ranging from lusty shouts for freedom to intrepid assaults on Government General outposts and vengeful mutilation of unlucky Kenpeitai, the Japanese gendarmerie. The second stage of the movement began in May and lasted until about April, 1920. During this stage, the independence activists changed their form of political activity from overt protest to covert planning and organizing, mostly in support of the Korean provisional government formed in Shanghai on April 10, 1919. The presence of additional troops from Japan, mass-arrest tactics, and stringent security measures made open protest activity unfeasible if not impossible.

The Government General juggled the available troops, withdrawing some from North and South P'yöng'an and Hwanghae, now regarded as safe, and assigned them to southern Korea, where the violence was rapidly spreading. On March 25 eight infantry companies were spread thinly over five southern provinces—North and South Kyöngsang, North and South Cholla, and South Ch'ungch'öng. The assignment was made with the hope that they would only be needed until March 30. But the Koreans kept up their attacks. Crowds formed everywhere in Seoul, stoning police stations and trolley cars. In five villages near Seoul, myön chiefs were threatened and myön offices attacked. In many places Koreans armed themselves with clubs and stones and attacked the closest police station or my on office. March 27 and 28 were frantic, tragic days as Koreans attacked in many localities only to be beaten off by troops and suffer heavy casualties. Thirty nine Koreans were killed in a single incident in Kyönggi Province. The governor general authorized new troop assignments on the 28th but the attacks continued. On March 31 Koreans armed with clubs, sickles, and other improvised weapons stormed gendarmerie units and police stations at several places in Kyönggi Province. They attempted, sometimes successfully, to burn the local public buildings—myön offices, post offices, police stations—and cut telephone lines. In one place the crowd tried to burn the stores of Japanese merchants. Many Koreans were killed and wounded in the assaults. Despite heavy casualties and against seemingly hopeless Koreans continued the fight. [...] April 2 was perhaps the bloodiest single day of the independence movement as Koreans continued their attacks on gendarmerie units, police stations, myön offices and school buildings. Demonstration marches were a thing of the past: these crowds were prepared to fight.Below is a list of casualties on the Japanese side:

In a lengthy recounting of a violent protest in Sacheon, Pyeongannam-do on March 4, which Baldwin describes as a "typical demonstration that began peacefully and ended in violence," three Korean police officers are reported as being killed in addition to a Japanese police officer, which makes clear that the numbers above do not include Korean Government General employees, suggesting that more people died than are listed. Most ironic in the assertion that the Samil Protests were peaceful is this statement by Baldwin:

Because of continued Korean violence, the Government General requested troops from Japan, which served to further discredit Japanese rule in the colony and provided additional incentive for the Hara administration in Tokyo to make reforms. Violent forms of participation appear to have been most important in changing Japanese policy.Additionally, the Jeam-ri massacre (looked at here) is better explained as the culmination of escalating violence on both sides rather than an out-of-the-blue mass killing by the (evil) Japanese.

The tale of "peaceful Samil demonstrations" serves the cause of depicting Koreans as a peaceful people beset upon by marauding outsiders; that is to say, victims with no responsibility for their actions. What better way to depict this fairy tale than a children's book about Yu Gwan-sun from the 한국 위인 전집 (Great people of Korea Collection) published by 노벨과 개미(looked at in more detail here):

Evil Japanese:

Peaceful, victimized Koreans:

Returning to the Joongang Daily article:

Han also found that only one publisher, Jihak Publishing, described the patriot [Yoo Gwan-sun] in its text. In contrast, four out of seven Japanese contemporary history textbooks included Yoo.The omission of Yu Gwan-sun from Korean textbooks is rather interesting. She's become an icon of the independence movement, much as Sin Mi-seon and Sim Hyo-sun became icons for those protesting the presence of USFK in Korea. Here is a poster which was once on the wall of the Yu Gwan-sun Underground Cell building at Seodaemun Prison:

Can you imagine any of the male icons of the Korean independence movement being depicted in this way? Besides being the oddly cheerful face of the fight for independence, she's often depicted as the embodiment of victimization (and thus embodies Korea throughout its entire history, according to some nationalist takes on Korean history). Here she is in the 'Great people of Korea Collection' book about her:

She also helps sell chicken, apparently (from 2005):

The final paragraph of the Joongang Daily article offers this short biography of Yu:

Yoo (1902-1920) was a prominent independence movement activist who was one of the organizers of the March 1 movement. She eventually faced torture at the hands of Japanese officers and died in prison in September 1920. When her family asked for her body to be returned to them, Yoo’s body was returned cut into pieces.In truth, most of the "organizers" of the movement offered themselves up for arrest after reading the declaration on March 1, essentially robbing the movement of its most respected leaders at its very inception. Yoo certainly organized protests in Cheonan after leaving the Ehwa school girl for girls, but is more likely remembered because she was a student at a prominent missionary school, and because she is the perfect symbol of innocence brutally snuffed out by the brutal Japanese. The main problem I have with the paragraph above, however, is that she was certainly not "cut into pieces." As is described by Jeannette Walter, an English teacher at Ehwa, in Donald Clark's "Living Dangerously in Korea (The Western Experience 1900-1950),"

Yu Kwansoon, a little sixteen-year-old girl, died in prison. We had her body brought back to the school, and the girls prepared cotton garments for her burial. [...] However, when I was in Korea in 1959, I was interviewed by a group from Kwansoon's school, and I assured them on tape that her body was not mutilated. I had dressed her for burial.One wonders if it is Rep. Han Sun-kyo or the Joongang Daily that is responsible for that canard once again being trotted out. A disservice may be have been done to the memory of the Samil Movement, but I'm not convinced its the textbook makers who are responsible.

Labels:

Colonial Era,

Education,

Japan,

Media,

Protest,

Xenophobia or Nationalism

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)