Government Information Agency chief Kim Chang-ho said Wednesday a policy meeting agreed the list of those to be stripped of decorations will be finalized in a Cabinet meeting next month. The move follows a legal revision that empowers the home affairs minister to propose withdrawing medals without consulting the agencies at whose recommendation they were awarded.The Korea Times continues:

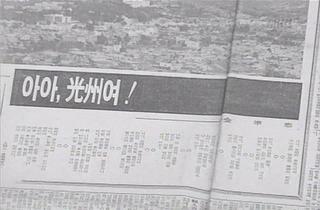

Chun was deeply involved in the crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in Kwangju in 1980, for which he received the Taeguk distinguished service order (DSO), the officials said.

Roh, successor of Chun, was also awarded with the Ulji DSO for his role as a security commander during the Kwangju movement. The number of people to be stripped of state medals is estimated at 67, including Chun and Roh, according to the officials.

Despite the Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs saying they would wait for the outcome of the defense ministry probe into the 12.12 incident and the Kwangju uprising before stripping anyone of their power, on Dec. 12, the 26th anniversary of Chun's coup, Prime Minister Lee Hae-chan brought up the issue at a meeting of senior officials. He was quoted as saying, "Please review the procedure to cancel the state orders for those who trampled on the pro-democratic movement in Kwangju with force."

The Chosun Ilbo put it a little differently:

Earlier, Prime Minister Lee Hae-chan urged ministers to be fair in deciding who deserves to be stripped of their medals given their role in the coup, adding no exception should be made for the two former leaders.It does sound like the home ministry is getting a little prodding from above, if what the Korea Times wrote is true. Had this come out earlier, perhaps Kim Dae-Joong (the right-wing columnist, not the former president) could have referred to it specifically in his list of ways in which the ruling party is trying to broaden its support base. At any rate, for more information about the background to this decision, I wrote about it here.

Speaking of the defense ministry probe into its past, yesterday saw the release of an interim report which focused on the 'Nokhwa' or 'greening' movement, and the Silmido incident. (More information about this probe can be found here.) Untangling the information about the Nokhwa program is a bit of a challenge, as three articles that were published yesterday about this report say different things.

As the Korea Times reports:

Pastor Lee Hae-dong, 71, former democracy activist, heads the committee composed of seven civilians and five military officials.

Chun directed then Defense Minister Choo Young-bok to draft students involved in democratic movements to frontline units on April 2, 1981, according to a 1988 dossier of the Defense Security Command (DSM). "Government agencies were found to have systematically implemented the plan, dubbed `Nokhwa (reeducation program),'" Lee said.

Under the Nokhwa program, which started on Dec. 1, 1981, the Chun government conscripted more than 1,100 student activists against their will, he said. Of them, six were found to have killed themselves, the panel said.

The Joongang Ilbo continues:

The Chosun Ilbo continues:The Defense Security Command, the military's branch responsible for intelligence as well as internal security, compiled a list of 1,121 college students who were marked by the government as troublemakers and then sent more than 1,100 of them to fulfill their military service at the De-Militarized Zone, after coordinating with other government organizations.

In 1988, when the government first investigated the case, the number of college students on the government's "black list" was initially announced as 447, and only 265 were said to have been drafted.

The committee further revealed that drafted students were sent to front line units regardless of their specialties and were continuously monitored by personnel from the security command. Some students under conscription age or who didn't meet the physical requirements for military service and so should have been exempted from military service were still drafted.

Under the “Nokhwa” program designed to emasculate the democracy movement, the Agency for National Security Planning conscripted student activists and subjected them to re-education programs with the aim of turning them against their comrades on campus and using them as spies. The committee found that 1,121 [the Korea Times says 1,200] -- 900 forcefully conscripted student activists and 300 ordinary conscripts -- were thus enlisted. The agency established a department to supervise them on Sept. 6, 1982 and scrapped it in December 1984.You end up with several dates: April 2, 1981, Chun gives the order to compile lists of students for military service; Dec. 1, 1981, the program begins (presumably meaning conscription for DMZ service begins); Sept. 6, 1982, a department is established to monitor the student activist spies; December 1984, the program ends. Whether the idea of using them as spies was thought of from the beginning or whether the plan evolved (from getting them out of the way and monitoring them while serving in the DMZ, to using them to spy on their colleagues) is something I'm curious about. Exactly how this program was related to the Samcheong Re-education camps, which would have preceded it, is also something I'd like to know more about.

The Joongang Ilbo has an article about 'Mangwon', or informants, and uses the 'Nokhwa' program as an example, but this article about the film 'Spying Cam', with it's Korean title 'Frakchi' says that:

``Frakchi,’’ which comes from the Russian word ``fraksiya,’’ refers to a government spy who infiltrated students’ organizations during the period of military dictatorship in Korea.Anyone have any idea which word was used at the time of the Nokhwa program?

[There's more to come but I'll just post this for now...]