After Japan's surprising victory over China in 1895, France, Germany, and Russia forced Japan to give up the Liaodong penninsula. Despite Japan's victory, these European powers had little respect for her as a rising 'imperial' power, and most certainly did not want her moving into Chinese territory. But by 1922, when the above map was published in The Times Atlas, titled The Japanese Empire, she had beaten Russia and gotten the Liaodong penninsula back, was recognized as having an 'Empire', and had even managed to get the western powers to acquiesce to the annexation of Korea. How did it happen? One important factor is discussed in Korea's Fight For Freedom (1920), where F.A. McKenzie wrote this of Japan's actions in the years immediately prior to Korea's annexation:

After Japan's surprising victory over China in 1895, France, Germany, and Russia forced Japan to give up the Liaodong penninsula. Despite Japan's victory, these European powers had little respect for her as a rising 'imperial' power, and most certainly did not want her moving into Chinese territory. But by 1922, when the above map was published in The Times Atlas, titled The Japanese Empire, she had beaten Russia and gotten the Liaodong penninsula back, was recognized as having an 'Empire', and had even managed to get the western powers to acquiesce to the annexation of Korea. How did it happen? One important factor is discussed in Korea's Fight For Freedom (1920), where F.A. McKenzie wrote this of Japan's actions in the years immediately prior to Korea's annexation:They had carefully organized their claque in Europe and America, especially in America. They engaged the services of a group of paid agents--some of them holding highly responsible positions--to sing their praises and advocate their cause. They enlisted others by more subtle means, delicate flattery and social ambition. They taught diplomats and consular officials, especially of Great Britain and America, that it was a bad thing to become a persona non grata to Tokyo. They were backed by a number of people, who were sincerely won over by the finer sides of the Japanese character. In diplomatic and social intrigue, the Japanese make the rest of the world look as children. They used their forces not merely to laud themselves, but to promote the belief that the Koreans were an exhausted and good-for-nothing race.Or as a comment on my last post described Korea at that time, "a country filled with a deep spiritual and physical sickness."

One of the more interesting examples of a contemporary foreign apologist for Japan's designs on Korea was George Trumbull Ladd, who wrote In Korea with Marquis Ito, published in 1908. A fascinating review of this book can be found in Scott Burgeson's book Korea Bug. Needless to say, his review of In Korea with Marquis Ito, which considers both the 'vitriol' with which he wrote as well as some of the hard lessons Koreans could take from it, is nowhere near as dismissive of the book as the 2001 Korean Herald review which first made me aware of it (here; ok, that's autotranslated from French, but you'll get the idea). Long out of print, it has actually very recently been reprinted, if anyone is interested).

At any rate, after undertaking a great deal of pioneering research in the field of psychology, and retiring from Yale, Ladd and his wife made their third trip to Japan in 1906. On the first page of his book, Ladd tells two stories related to the Russo-Japanese War he heard while en route to Japan, and explains why he's telling them:

...they are repeated here because they illustrate the code of honor whose spirit so generally pervaded the army and navy of Japan during their contest with their formidable enemy. It is in reliance on the triumph of this code that those who know the nation best are hopeful of its ability to overcome the difficulties which are being encountered in the effort to establish a condition favorable to safety, peace, and prosperity by a Japanese protectorate over Korea.While the first page alone already gives the reader a pretty clear idea of how he feels about Japan regarding its relationship with Korea (in fact, Burgeson characterizes the book as "an answer in search of a question, one in which the author's mind about his subject has been fixed at the outset, and refuses to open itself to any changes or new discoveries."), he goes on to explain that while he had planned to lecture on philosopy and psychology, as he had done on his previous trips in 1892 and 1899,

The thought of seeing something of the "Hermit Kingdom" (a title, by the way, no longer appropriate) had been in our minds before leaving America, only as a somewhat remote possibility. Not long after our arrival in Japan the hint was several times given by an intimate friend, who is also in the confidence of Marquis Ito, that the latter intended, on his return in mid-winter from Seoul, to invite us to be his guests in his Korean residence.At a garden party, Ladd finally meets Ito:

After an exchange of friendly greetings almost immediately the Marquis said: 'I am expecting to see you in my own land, which is now Korea'; and when I jestingly asked, 'But is it safe to be in Korea?' (implying some fear of Russian invasion under his protectorate) he shook his fist playfully in the air and answered: 'But I will protect you.'Later, Ladd recounts a private meeting with Ito:

I was to feel quite independent as to my plans and movements in co-operating with him to raise out of their present, and indeed historical, low condition the unfortunate Koreans. In all manners affecting the home policy of his government as Resident General, he was now a Korean himself; he was primarily interested in the welfare, educationally and economically, of these thirteen or fourteen millions of wretched people who had been so long and so badly misgoverned. In their wish to remain independent, he sympathized with them. The wish was natural and proper; indeed, one would be compelled to think less highly of them, if they did not have and show this wish. As to foreign relations, and as to those Koreans who were plotting with foreigners against the Japanese, his attitude was of neccessity entirely different.[...] Japan was henceforth bound to protect herself and the Koreans against the domination of foreign nations who cared only to exploit the country in their own selfish interests or to the injury of the Japanese.Ito puts the best spin possible on Japan's reasons for wanting to swallow Korea, and this, Burgeson writes, is essentially the main argument of the book. Ladd goes on to write disparagingly of Korea's history (as told to him by the Japanese) and largely sees Korea and Koreans as being dirty, backward, and in need of Japanese tutelage. In his description of the king, he said:

His face wore a pleasant smile with which he is said to greet all foreigners... although it's asthetical effect is somewhat hindered by a bad set of teeth.Later, when he dismissed as a forgery a document shown to him by Koreans which supposedly illustrated Japan's plans to annex Korea, he wrote:

The silliness of mind, the almost hopeless and incurable credulity and absolute absence of sound judgement which characterizes, with exceedingly few exceptions, the political views and actions of even the official and educated class in Korea, was the impression made upon me by this, as by all my experiences during my stay in the land.It's interesting how, when I reread this review the other day, some of Ladd's phrases seemed very familiar, mainly because I had just read the four chapters pertaining to Korea in James Creelman's 1901 book On the Great Highway, (shades of Hunter S. Thompson?) which recount his experiences covering the 1894-1895 Sino-Japanese war. Creelman was, to use a modern term, embedded in the Japanese army along with other journalists like Frederic Villiers.

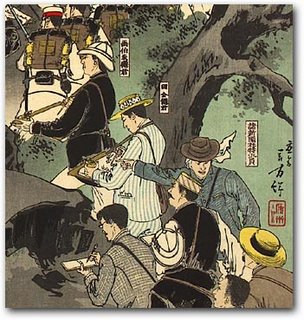

[Edit] Foreign correspondents with the Japanese Army.

[Edit] Foreign correspondents with the Japanese Army.Detail of Japanese woodcut taken from this page.

Japan was henceforth bound to protect herself and the Koreans against the domination of foreign nations who cared only to exploit the country in their own selfish interests or to the injury of the Japanese [as Japan wanted only to] raise [the Koreans] out of their present, and indeed historical, low condition.- then the following basically sums up the way they wanted their war against China over Korea spun in 1894:

The armies of Asiatic barbarism and Asiatic civilization met on this ground to fight the first great battle of the war that ended in the fall of Wei-Hai-Wei and Port Arthur; and here Japan emancipated the helpless Corean nation from the centuried despotism of China.The book covers the war from the mid-September battle for Pyongyang to the late November battle of Port Arthur. In those two months, he would have constantly been receiving the Japanese line on the war and their reasons for waging it. Just how close he was to the Japanese officers whose campaigns he was recording, and how important his reporting was for them is illustrated here:

That night, on my way back to Ping Yang, I found the main Japanese fleet at the mouth of the Tai-Tong River. Admiral Ito had defeated the Chinese fleet, and had just fallen back on the Corean coast for repairs and ammunition. It was a great opportunity for a war correspondent. No other newspaper man had reached the victorious fleet, and fortune had given to me the first story of the most important naval fight of modern times -- the battle of the Yalu.Later he tells us that "There was nothing to eat in the little house where I slept, but the field-marshal sent me a bottle of Burgundy." The good impression the Japanese made on him was able, several years later, to overcome the fact that he witnessed this:

When I boarded the flagship Hashidate, Admiral Ito was asleep, but he dressed himself and sent for his fleet captains in order to help me out with the details of the conflict.

As the Japanese admiral sat at his table, surrounded by his officers, with the rude charts of the battle spread out before him, he looked like a sea-commander -- tall, eagle-eyed, square-jawed, with a sabre scar furrowed across his broad forehead; a close-mouthed man whose coat was always buttoned to his chin. Bending over the maps and smoothing out the paper with his sinewy, big-knuckled hands, the lamp-light gleaming against his powerful face, he was a man not easily forgotten.

And when the tale of that thrilling struggle on the Yellow Sea was over, the admiral turned to me smilingly.

"It is a big piece of news for you," he said.

"Yes," I answered, "but I have received a still greater piece of news."

Then I drew from my pocket the cablegram announcing the birth of my boy, and read it.

"Good!" cried the admiral. "We will celebrate the event. Steward, bring champagne!"

Standing in a circle, the admiral and his captains clinked their glasses together and drank the health of my little son.

"I saw a man who was kneeling to the troops and begging for mercy pinned to the ground with a bayonet while his head was hacked off with a sword...An old man on his knees in the street was cut almost in two...Frederic Villiers' account of the Port Arthur massacre can be found here. The Japanese version of events can be found here, while the outcome for Creelman, personally, is recounted to his wife Alice in a December 21, 1894 letter from Yokohama:

"All day the troops kept dragging frightened men out of their houses and shooting them or cutting them to pieces...All through the the second day the reign of murder continued. Hundreds and hundreds were killed. Out on one road alone there were 227 corpses...

"Next day I went...to see a court-yard filled with mutilated corpses. As we entered we surprised two soldiers bending over one of the bodies. One had a knife in his hand. They had ripped open the corpse and were cutting the heart out. When they saw us they cowered and tried to hide their faces.

"I am satisfied that not more than one hundred Chinamen were killed in fair battle at Port Arthur, and that a least 2000 unarmed men were put to death. It may be called the natural result of the fury of troops who have seen the mutilated bodies of their comrades, or it may be called retaliation, but no civilized nation could be capable of the atrocities I witnessed at Port Arthur."

I am now the general target for abuse in Japan simply because I have told the truth about Port Arthur. I knew in advance that to lay the naked facts before the public would mean the instant activity of the vast enginery of abuse maintained by the Japanese government and so I considered my duty call. I could not as a reputable journalist nor as an American attempt to conceal any fact of the great crime. It was too monstrous, too cold, too long continued.....[emphasis added]Less than a decade later, despite witnessing such a 'great crime', and becoming a 'target for abuse' for revealing it, he was able to write

Whatever I may have written of that three days' slaughter at a time when Japan was seeking admission to the family of civilized nations, it is only just to say that the massacre at Port Arthur was the only lapse of the Japanese from the usages of humane warfare. A witness for civilization, I could not remain silent in the presence of such a crime. The humanity and self-control of the Japanese soldiery during the historic march of the allied nations to Peking, seven years later have redeemed Japan in the eyes of history. The Japanese have demonstrated to the world that their civilization is substantial.Creelman, despite the fact that he thought so much of Japan, did not see Korea in quite the same way Ladd did.

The traveller in Corea is bewildered by the effects of three thousand years of hermit life upon this strange people. They are not savages. Thirty centuries of civilization are set down in their literature. Nowhere else in the world have I seen such magnificent specimens of physical manhood. The ordinary European is a pygmy among the tall, straight, powerful Coreans. An indescribable gravity and dignity of manner lends itself to the impressive grace and strength and the noble features of this ancient race. As the men become old they grow long beards, which add to their naturally majestic bearing.

Yet the Coreans are the emptiest-headed, most childlike, and most generally foolish people among civilized nations. They are the grown-up children of Asia. Their ignorance is not like the ignorance of Central Africa. Hundreds of years ago, they inspired Japan with the love of art, and their literature is as old as Egypt. They are gentle and meditative. Throughout the Corean peninsula, stately quotations from the noblest Chinese odes are painted on the public buildings, in the quaint summer pagodas, and on the walls of dwelling houses. Their very battle flags are inscribed with philosophic sayings. But the Coreans are drugged with abstract scholasticism and demonology. They are credulous almost beyond belief.Creelman's descriptions of Korean reasoning, or lack thereof - "emptiest-headed, most childlike, and most generally foolish people"; "credulous" - sounds very similar to what Ladd would write over a decade later: "The silliness of mind, the almost hopeless and incurable credulity and absolute absence of sound judgement..." Just in case one were to think this was the common perception at the time, Isabella Bird Bishop had this to say:

The Koreans certainly are a handsome race... Mentally the Koreans are liberally endowed... The foreign teachers bear willing testimony to their mental adroitness and quickness of perception, and their talent for the acquisition of languages, which they speak more fluently and with a far better accent than either the Chinese or Japanese. They have the Oriental vices of suspicion, cunning, and untruthfulness.Bishop's opinion of Korean mental ablilities is different, but shares in common with Creelman an appreciation for Koreans physically - "a handsome race"; and "magnificent specimens of physical manhood", respectively (though it goes without saying Creelman presents almost every story or observation with a rather dramatic flair). Creelman and Ladd also differed on their opinions of the King of Korea. Creelman presents the reader with this description:

He stood behind a table, in front of a gaudily upholstered European chair, with his small, nervous hands crossed lightly over his ceinture, -- a slender, shy man, with an oval face, thin, silky mustache and chin beard, a kind, voluptuous mouth, and soft, dark eyes. He had the eyes of a beautiful girl. When he smiled he hung his head on one side, half closed his eyes, looked straight at us, and opened them slowly with the expression of a bashful woman.Ladd wasn't as appreciative:

His face wore a pleasant smile with which he is said to greet all foreigners... although it's asthetical effect is somewhat hindered by a bad set of teeth.Ladd saw Korea as dirty and feared getting sick; Creelman, while describing Chemulpo (Incheon) as dirty, described Seoul as "the picturesque capital of Corea", at odds with Bishop's description of Seoul only a few months earlier.

One has to wonder at the difference (and similitarities) in these men's view of Korea, and what it is attributable too. One could certainly speculate about the strength of their characters and their abilities to think for themselves instead of believing uncritically what the Japanese were spoon-feeding them; in that case the principled war correspondent would seem to have been better able to think for himself than the retired academic who acted as an English-language conduit for the views of the powerful men who were wooing him. While this interpretation may have merit, more likely it was the difference in the messages the Japanese were feeding these men.

During the Sino-Japanese War, Creelman spoke of the meeting of the "armies of Asiatic barbarism and Asiatic civilization". The Chinese were to be made to look semi-barbaric (a task made easier by the behavior of their troops), while the Japanese were to be portrayed as a member of the family of civilized nations. Much of this was due to the desire on Japan's part to be taken seriously by the west (with insecurity playing a role) , and so their troops were generally very well behaved throughout the campaign - at least in front of the foreign correspondents. Creelman, travelling by ship to Manchuria, wouldn't have seen the behavior of the Japanese troops who occupied Pyongyang after their victory there:

15,000 - four-fifths of its houses destroyed, streets and alleys choked with ruins... Everywhere there were the same scenes, miles of them... Phyongyang was not taken by assault ; there was no actual fighting in the city...While this is certainly not comparable to the atrocities that took place in Port Arthur, leaving a city of 80,000 in ruins is not something I would call very civilized. Beyond portraying themselves as polite warriors fighting barbarians, the Japanese further wanted to be seen as "emancipat[ing] the helpless Corean nation from the centuried despotism of China." In order to make the Koreans seem, indeed, helpless, one would think they would have to be made to seem incompetent or even stupid, which is how Creelman portrays them. That's how Ladd portrays them as well, though Creelman still has nice things to say about Korean civilization, history, and physical appearance.

When the Japanese entered and found that the larger part of the population had fled, the soldiers tore out the posts and woodwork, and often used the roofs also for fuel, or lighted fires on house floors, leaving them burning, when the houses took fire and perished. They looted property left by the fugitives during three weeks after the battle... Under these circumstances the prosperity of the most prosperous city in Korea was destroyed.

By the time Ladd came to Korea, however, Japan, having beaten rival Russia, was taking great "effort to establish a condition favorable to safety, peace, and prosperity" for itself in Korea. In order to seem justified in this, their 'code of honor' and civilization had to be emphasized. They had to seem as though they were trying to "raise out of their present, and indeed historical, low condition the unfortunate Koreans." Now the Koreans' 'wretchedness' and 'low condition' had to be made to seem historical, and that only the civilized Japanese could aid them. There could be no more mentions of "Thirty centuries of civilization", or of their "indescribable gravity and dignity of manner", or "impressive grace" and certainly nothing like "Hundreds of years ago, they inspired Japan with the love of art". All of that had to go. As F.A. McKenzie said above, they had "to promote the belief that the Koreans were an exhausted and good-for-nothing race."

Ladd was more than up to the task. His disparaging view of Korea was no doubt coloured by the Japanese guides who explained the country's history and culture (or lack thereof) to him. As F.A. McKenzie wrote in The Tragedy of Korea (1908):

One distinguished foreigner, who returned home and wrote a book largely given up to laudation of the Japanese and contemptuous abuse of the Koreans, admitted that he had never, during his journey, had any contact with Koreans save those his Japanese guides brought to him. Some foreign journalists were blinded the same way.The opening of Korea's Fight For Freedom essentially consists of character references giving support to McKenzie; they also illustrate how Japan celebrated the foreigners who lauded them, and attacked those who criticized them.

"Mr. F.A. McKenzie has been abused in the columns of the Japanese press_ with a violence which, in the absence of any reasoned controversy, indicated a last resource... It is difficult to see how Mr. McKenzie's sincerity could be called into question, for he, too, like many other critics of the new Administration, was once a warm friend and supporter of Japan.

"In those days, his contributions were quoted at great length in the newspapers of Tokyo, while the editorial columns expressed their appreciation of his marked capacity. So soon, however, as he found fault with the conditions prevailing in Korea, he was contemptuously termed a 'yellow journalist' and a 'sensation monger.'"--From "Empires of the Far East" by F. Lancelot Lawson.

"Mr. McKenzie was perhaps the only foreigner outside the ranks of missionaries who ever took the trouble to elude the vigilance of the Japanese, escape from Seoul into the interior, and there see with his own eyes what the Japanese were really doing. And yet when men of this kind... have the presumption to tell the world that all is not well in Korea, and that the Japanese cannot be acquitted of guilt in this context, grave pundits in Tokyo, London and New York gravely rebuke them for following their own senses in preference to the official returns of the Residency General. It is a poor joke at the best! Nor is it the symptom of a powerful cause that the failure of the Japanese authorities to 'pacify' the interior is ascribed to 'anti-Japanese' writers like Mr. McKenzie."--From "Peace and War in the Far East," by E.J. Harrison. [emphasis added]And what were these 'official returns' of the Residency General? Andre Schmid's Korea Between Empires, 1895-1919 gives a description:

...the colonial authorities sought to disseminate to the West the rationale for their growing Asian empire... To this end, an elaborate propaganda campaign was launched by the Resident General Office and, after 1910, continued by the Governor General Office. For a Japanese-speaking colonial administration seeking to gain the West's support for its endeavors in Korea, this plunged the office into the task of preparing foreign-language materials about its endeavors. It's premier series, begun in 1907, was a glossy yearbook written in English entitled Annual Report on the Progress and Reforms in Korea, a less than subtle promotion of colonialism. During the first decade of publication, the yearbooks' format was a "before and after" presentation offering explanitory, pictorial, and statistical evidence of changes Japan had made on the penninsula since establishing the Protectorate. This approach could be applied to almost any topic, from hygiene to road systems, with the contrast achieved through the judicious choice of adjectives. Accordingly, the penninsula's financial condition before annexation was in the "wildest confusion," and expenditures were "wasted to no purpose". But after Japan's reforms, the foundation of Korea's finances was "firmer," and details of how these achievements had been accomplished were buttressed by reams of statistics. This contrastive effect was also captured in photographs, as in the case of two pictures of the Han River south of Seoul. A photograph of a bridge built under the new Japanese administration was placed next to a second photograph showing a few boats moving back and forth across the river, labeled "before the construction of the Iron Bridge."[emphasis added]A less than subtle, comparative, 'before and after' format using photos and phrases like "wildest confusion" (which in today's parlance might be "basket case")? I wonder if, when the Japanese developed this format for their propaganda purposes, they realized it might also be useful for justifying their colonial adventure long after the fact?

When I read of Japan's elaborate propaganda effort aimed at convincing the West that the Koreans were in need of Japan's aid, and that Japan, as a selfless, civilized country was trying only to help their neighbour, and that it was cataloguing the ways in which it was, in fact, modernizing Korea, I couldn't help but think of this passage in "Korea's Fight For Freedom":

Then Japan sought to make the land a show place. Elaborate public buildings were erected, railroads opened, state maintained, far in excess of the economic strength of the nation. To pay for extravagant improvements, taxation and personal service were made to bear heavily on the people. Many of the improvements were of no possible service to the Koreans themselves. They were made to benefit Japanese or to impress strangers. And the officials forgot that even subject peoples have ideals and souls. They sought to force loyalty, to beat it into children with the stick and drill it into men by gruelling experiences in prison cells. Then they were amazed that they had bred rebels. They sought to wipe out Korean culture, and then were aggrieved because Koreans would not take kindly to Japanese learning. They treated the Koreans with open contempt, and then wondered that they did not love them.

14 comments:

Another excellent piece!

They sought to wipe out Korean culture? Then why was the first dictionary of Korean language for normal school published in 1930?http://english.chosun.com/w21data/html/news/200402/200402260026.html

It doesn't make sense.

Anyway, I think you should read these following books. "Offspring of Empire" by Carter J. Eckert.

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0295975334/qid=1143453922/sr=1-1/ref=sr_1_1/103-1335562-6211855?s=books&v=glance&n=283155

"The Wealth and Poverty of Nations" by David S. Landes

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0393318885/qid=1143454428/sr=1-2/ref=sr_1_2/103-1335562-6211855?s=books&v=glance&n=283155

Matt,

Here is a Chosunilbo newspaper which was published in 1940. They were still allowed to use Hangul.

http://blog.ameba.jp/user_images/be/b9/10003227193.gif

And the following is a part of Miyukimori school list of graduates for 1942. This shows Koreans students in Japan were still allowed to use Korean names.

http://park6.wakwak.com/~photo/image/tb02.jpg

When Korea was a vassal state of China, every official document was written in Chinese character. The first newspaper written in both Chinese character and Hangul was Kanjyo Shunpo (Seoul Weekly Report) and it was published by Yukichi Fukuzawa in 1886. Anyone who claim the Japanese sought to wipe out Korean culture is just ignorant. If the Japanese government had intended to eradicate the Korean culture, it would not have allowed the publication of Korean language newspapers, books, movies, songs etc, or Korean education in schools in the first place.

Excellent stuff. I'm going to give you a puff at Frog in a Well when I get a moment.

By the way, thanks for the kind words Owen, and pk.

A list of Korean movies released during annexation.

http://kaokaosama.hp.infoseek.co.jp/garakuta/cinema3.html

Some of Korean songs released by Japanese record companies in the late 1930's.

http://syasinsyuu.cool.ne.jp/corea/corea22.jpg

http://syasinsyuu.cool.ne.jp/corea/corea21.jpg

To say the Japanese sought to wipe out Korean culture is just wrong and it misleads people.

As for the Samil uprising, I recommend you to read this article.

http://www.ddanzi.com/ddanziilbo/46/46so_3002-2.htm

The Korean film industry began in the early 1920s during the period of political relaxation that followed the 3.1 movement. By 1937, "Japan had invaded China, and the Korean film industry would become transformed into an instrument of the Japanese propaganda effort. In 1942, Korean-language films were banned outright by the government." [Link]

As I've said, the period between 1920 and 1937 was a more relaxed period and these examples you've provided are from that period. The pictures of the records are pretty neat, though.

Some of the Japanese socialists mentioned in that article were actually anarchists (the 1910 'Emperor Assassination Plot' that is mentioned involved the execution of 10 prominent anarchists, including Kotoku Shusui); The 2.8 declaration was something I'd never learned much about, but found some articles related to it (as well as a translation of the declaration) here. [1 2 3]

This page also talks about the anarchist movement in Korea (though the book it's based on is said to exaggerate). Many of the anarchists and socialists in Japan were anti-imperialist, so I imagine they would have been in solidarity with the Korean students there. Suffice to say, Korean students in Japan were much more likely to learn about radical ideas there than in the much more repressive climate of Korea in the 1910s. One thing I've always wondered about were the Gandhian aspects of the 3.1 uprising and where the Koreans learned of those ideas - whether they heard of Ghandi's civil disobedience in South Africa, or whether it was developed independently.

As time pass, as our memories falter, as number of Japanophiles increase, I predict more and more historic revisionists to rise up and change everything around to make Japan look good. In 50 years, the Japanese books will say Japan didn't colonize Korea, Japan was just helping Koreans to modernize. In 50 years, Japan didn't attack China, China attacked Japan. In 50 years, America nuked Japan for no good reasons. In 50 years, Tojo was a good man who promoted democracy in Japan. In 50 years, bull shit will become truth.

Er... the US did nuke Japan for no good reason.

[But then maybe we don't want to get into that one.]

If you can read Korean, I recommend you to read these following articles.

http://www.new-right.com/read.php?cataId=nr02000&num=1084

http://www.new-right.com/read.php?cataId=nr02000&num=1085

I wonder what the point of this post is but to say that the Japanese were better at diplomacy than the Koreans? Guess what, they still are.

Complaining about the adriotness of another country's diplomacy is sulking of the second best and also-rans.

Meanwhile Japan is able to maintain excellent relations with the US while Koreas relations with the US is in tatters. I wonder how Korea will try to pin that one on Japan.

did Korea write this post?

I wrote an article about this also.

http://zeroempty000.blogspot.com/2006/04/korealate-chosun-periodinterpretation.html

Mika seems a typical japanese.

Hirohito, a japanese king, officially claimed in his famous "speech of finishing war" to his ppl that The pacific war was begun for "the peace of the east asians", "and liberating asian ppl" from imperialists. and invaion of other nations were not his intent.

I think japanese ppl (or culuture) has some specialy talent of decieving themselves unconsciously...

Post a Comment