In a recent column about the Kwangju Uprising, Michael Breen wrote:

For today’s young people, the event is ancient history, as far away as the Korean War was for Kwangju’s victims, most of whom were also students.There are several things I could pick apart in his piece, but I'll just focus on the above sentence.

First, (and quickly), according to Linda Lewis, in Laying Claim to the Memory of May, students "comprised just 19.5 percent of the official victims, and were only a slight majority (fifteen of twenty-eight) of those killed on the last day (May 27) [...]"

Second, while the event may be 'ancient history' to young people in the rest of the country, for youth in Kwangju (at least during the month of May) it is not - or at least, when I visited the city during the 25th anniversary celebrations last year (as this person did) , it was clear that they've been taught never to forget it. Anyone interested in how the interpretations, perceptions, and memorialization of the uprising have changed over the past 26 years should read the aforementioned book by Linda Lewis, who was an eyewitness to the uprising.

When I arrived in Kwangju on May 21 last year, there was a large "Red Festa"('festival') in front of the Provincial Hall (which was the focal point of the uprising) where numerous displays, posters, and video, about the uprising could be seen. Numerous graffiti-covered buses with smashed windows stood in the street in front of the Provincial Hall, as they had on that day 25 years before, when the military had opened fire on the protesters. As I took in the displays I talked to a few high school students, and two of them told me proudly that their fathers had taken part in the uprising. Students also left post-it notes with messages on a board, one of which immediately caught my eye:

No one's surprised to see this in Kwangju, of course, but in retrospect it's funny when I think of one of the students who my friend talked to who complained about the money-obsessed people in Seoul who he thought didn't have good priorities, as I can't think of many middle or high school students I've taught who've been aware enough of politics at all to bother criticising a political party - even if the political awareness of the student who wrote this was as sophisticated as "GNP = bad". There were other visual touchstones of the uprising, such as the students pulling a cart of jumeok-bap (rice balls) , which represent the solidarity of the community during the days of "Free Kwangju", when people shared their food with the citizen's army, and women made large amounts of rice balls for demonstrators, as can be seen here and here (the latter photo being a rather prominent photo promoted by the city to reinforce the peaceful, orderly nature of the days when the military was outside of the city).

After taking in the displays, I watched the high school students re-enact the shootings of May 21, 1980, (which is why the buses were parked on the street). The students portrayed both the demonstrators and the soldiers.

After the 'troops' were in place, the sound of (recorded) gunfire was heard, the students fell, and the soldiers beat them - though there were probably more camera-phones present than the flailing batons they were recording.

Of course, it didn't end with this - the citizen's army eventually came to save the day, and then the students taking part in the re-enactment, as well as the spectators, walked towards a stage set up in front of the Provincial Hall, where a concert was set to begin (and during which, while the kids listened to hip-hop and pop artists, photos of the uprising were displayed on a large screen). Before reaching the stage, however, a large banner showing what was unfolding on that spot 25 years earlier was blocking the view. The crowd proceeded to tear strips off of it as they passed, which removed the bottom half of the banner - where the soldiers could be seen. Whether this was a coincidence, or a symbolic removing of the soldiers from the picture, or neither of these, I have no idea.

This was definitely the day for the youth to come out and re-enact an experience which is apparently not memorialized by the youth in Kwangju as a "scar on Korea's history" but instead as something to take civic pride in ("no other city stood up to the dictatorship"). I'm sure many who actually lived through the uprising, especially those who were injured, would rather put it behind them. Lewis, in her book, talks about how the city of Kwangju, and the national government, have been recasting Kwangju as an essentially peaceful democratic protest by focusing on the days of Free Kwangju and placing less emphasis on the violence that bookended these days. Don Baker, referring to Lewis' book, spoke of "how events can assume a role in history independent of the memories of those who experienced them", which sums this all up perfectly. Those who were in Kwangju in May 1980, who have solemnly visited the graves of those they lost, might well be appalled at this kind of memorialization, a "violent" and "exciting" event which the kids recreate and video with their phones. But the latter narrative of resistance, of Kwangju's uniqueness and, in the idea of Kwangju contributing to democracy, of its eventual triumph, is likely much more appealing to a younger generation of Koreans who have been brought up in relative affluence and who have no memory of the dictatorships. The brutality faced by those who stood up to Korea's former rulers may be as distant and unreal as ... a cartoon character?

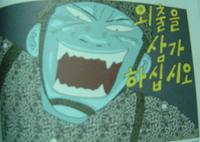

Perhaps that's one reason why we're seeing narratives of the uprising (produced in Kwangju) in cartoon form these days, from Nuxee, the 'mascot' of the Kwangju Uprising, to comic books obviously aimed at a young audience which tell the stories of both the heroes and victims of the uprising. Nuxee first appeared in 2000, the same year, Linda Lewis tells us, that the Kwangju Biennale (an art festival) was moved to the spring to coincide with the 5.18 anniversary celebrations. As Lewis relates,

Posters and T-shirts with the slogan "Millenium [sic] Long Glow - 5.18" and depictions of the new Kwangju Uprising 'Mascot' - Nuxee - appeared on the streets alongside banners proclaiming more traditional sentiments, such as "Let's keep the May spirit alive and drive out the American bastards!" This reimaging of Kwangju reflects, in part, the impact of new actors and groups in civic affairs.She describes many of these new groups and their attempts to move away from the "unbiased" sources of those who lived through the uprising (one example of this being the publication of the journalists' accounts found here) to move the focus away from the annual student protests against the American military, and to concentrate on the days of "Free Kwangju."

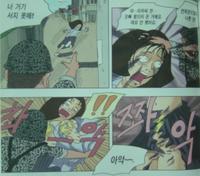

While, as Don Baker points out in the essay "Victims and Heroes: Competing Visions of May 18", ideas of who was victimized during the uprising have broadened out, in some cases, to include the paratroopers who took part, a 200 page comic I found in Kwangju (기영이의 5·18여행), which includes photos of the uprising, along with a simplistically drawn recounting of the events, has none of this. The soldiers are depicted as the embodiment of pure evil, such as in the photos below, one of which depicts a soldier stripping a teenage girl (which was common practice for prisoners of either sex), and later, raping her.

This girl, whose name, Jo Hyeon-jeong, is clearly pointed out (on another page), isn't just meant to represent one of many victims; the comic depicts what happened to specific people, and is clearly playing a part in mythologizing these 'heroes and victims' in order to instill civic pride (and some measure of a feeling of victimization) amongst the younger generation. While there may be competing visions of what occurred in Kwangju even amongst the groups there, many of the narratives that continue to be produced in the city of Kwangju will view what happened in much more personal terms than those from other regions of the country.

I made my way out to the 5.18 National Cemetery the next day. In the comments to the Marmot's post about the 25th anniversary of the Uprising, Plunge provided a link to this page, which shows where each victim is buried. Those buried there include those who died during the uprising, as well as those injured (or tortured in prison afterward) who have died since.

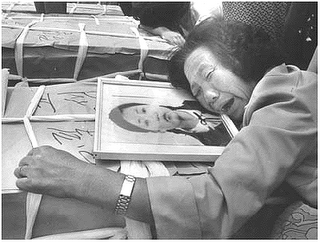

Due to the time wasted touring Kwangju's suburbs (due to some rather faulty directions from the tourist office regarding buses), I didn't get a chance to see the Mangwol-dong cemetery, where the victims were originally interred. Most were buried there on May 29, 1980, when this picture was taken:

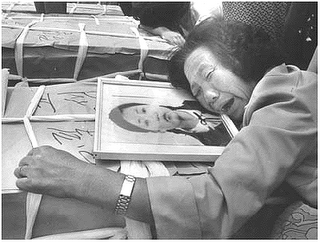

Looking into this photo led me to another way in which the uprising has been commemorated in Kwangju. You'd have to have a heart of stone not to be moved by this photo, which brings to mind something journalist Norman Thorpe wrote:

I was reminded how each family had had great hopes for whomever had died, especially for those who had been students. I had just met some of those students in hospitals--lucky ones whom the bullets had only wounded. But here was something I hadn't thought about. Some of the families were so poor that they could only bring a coffin by bicycle. And now in a wrenching upheaval, the focus of their hope was gone.When I first saw this photo, couldn't help but think about how young the girl in the picture looked. Some time later, I found a Korean website with photos of various demonstrations that took place during the post-war years, and this photo was there. The caption underneath read "박금희의어머니" - Bak Geum-hui's mother. The name stuck in my mind, and I couldn't help but wonder about how old she was, and how she died. Later, I reread the article "Nightmare in Idyllic Pastures", by Gebhard Hielscher and found this passage:

Inside the small gymnasium opposite the provincial administration building, meanwhile, the dead already identified as victims of the bloody massacre of Kwangju are being mourned. Exactly 60 coffins have been lined up in orderly fashion--most are covered with white cloth, bound with ropes and decorated with the flag of South Korea. Photos of the dead, the frames wrapped in mourning crape, have been placed on some of the coffins. On a make-shift altar, incense is burned, a cardboard box is stuffed with donated bank-notes.

A young man desperately beats one of the wooden boxes yelling: "My younger brother is in here--how could Korean soldiers shoot on Koreans!" No one attends to the coffins numbered 56 to 58. They contain a whole family: a boy of only seven years, barely a first-grader in school, his mother and his father. Somebody placed a bunch of white chrysanthemums on the little boy's coffin.

In the next row a group of young girls has gathered. They are students of Shuntae Economic High School in Kwangju. They still cannot comprehend that one of their classmates is lying dead before them. Their voices choked in tears, the girls sing a farewell song. Then one of them turns around and, facing the people of the platform, makes a dramatic appeal: 17 year old Park Keun Hee shall not have died in vain. At the end everybody in the hall starts singing South Korea's national anthem. "Long live the Republic of Korea, long live democracy."

Despite the misspelling, this seemed to describe the scene at her coffin. I now knew her age, but not how she had died. The book Memories of May 1980: A Documentary History of the Kwangju Uprising in Korea, has numerous descriptions of those who suffered death and injuries during the uprising, but she didn't appear - until I found this passage, under the heading "Examples of Casualties during the Evacuation of the 11th and 7th Brigades from Chosun University on May 21st":

Pak Chan-uk - Was driving by Chiwon-dong bus terminal that evening in blood donation vehicle towards Provincial Government Building to donate blood and transport patients. Suddenly, armored vehicles evacuating towards Hwasun began shooting randomly; was shot in the left shoulder and taken to Christian Hospital to receive surgery. One man and Pak Kum-hui, a student from a girls' high school returning home after donating blood, who were riding in the vehicle, were killed by the shooting.Strangely enough, this brought to my memory something I'd quoted from Linda Lewis' book in the comments to the Marmot's Kwangju post last year, about the testimony of American missionary Martha Huntley, who worked at the Kwangju Christian Hospital.

In two hours our hospital alone received 99 wounded and 14 dead. Among the wounded was a 9 year old boy who was shot in the legs. Our first dead was a middle school girl; the second was a commercial high school girl who had donated blood at the hospital 15 minutes earlier and was shot by the troops when she was being returned home in a student vehicle. We received 5 patients with spinal cord injuries, many of whom will never walk again. One was 13 years old. We had patients who lost eyes, limbs, and their minds.[Emphasis added]It was odd to realize that this person, whose death I had been so curious about, had, unbeknownst to me, been described in a passage I had recently quoted.

To interrupt, here is more information about her death from an August, 2007 Joongang Ilbo article: Haunted by the death of a high school girl.

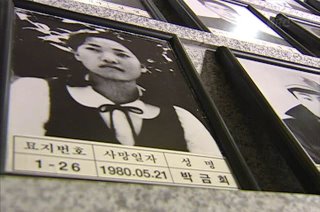

On May 21, 1980, Ahn Sung-ryea, 43, a supervising nurse at the Christian Hospital here found herself amid a bloody pile of dead bodies and gunshot victims. She had been at the hospital for three days treating patients who filled almost every inch of space in the building.[...]Park Geum-hui's picture appears in the Photographic Memorial Hall at the 5.18 National Cemetery...

Ahn and her fellow nurses, doctors and janitors were forced to take turns drawing blood from their own arms to supply desperately needed transfusions. Ahn was especially glad when a group of citizens arrived at to the hospital to donate blood. Park Geum-hui, then a high school student with braided hair, was one of them.

“Geum-hui looked at me and said, ‘Ma’am, I couldn’t just sit at home and study. There’s no use going to college if I cannot do anything about what’s happening in my own town,’ ― then she was gone,” Ahn recalled. About an hour later Park returned to the hospital as a mangled corpse. “Her blouse was soaked in blood and she was covered with dust,” Ahn said, her voice growing hoarse. “I collapsed and burst into tears. I cried out ‘The soldiers are evil!’ over and over. My heart was broken.”

...where her final resting place can also be found.

I later found this page (in Korean) about her death, but more importantly, I found a KBS documentary in which her death (and it's memorialization) were looked at. The documentary draws on accounts of the mass shootings, of the chaos in the hospitals, and the numerous people who donated blood (dramatized in the 1995 TV drama Sandglass (모래시계)), which led to her death. It even shows the hospital's documentation of her death (after being shot in the abdomen):

The school she attended has a sign commemorating her as a "Flower of May 1980":

The use of flower imagery is interesting; I don't know if Choi Yun's 1988 novella There a Petal Silently Falls (translated into English here: Part 1 ; Part 2), upon which Jang Sun-woo's 1996 film 'A Petal' was based, was the first to use this kind of imagery or not. At any rate, at the school pictured above, the documentary goes on to show teacher Bak Ok-hui directing students performing a play titled "Our sister, Bak Geum-hui" (우리 언니 박금희) (more about this play, including photos, can be found here (scroll down)). This portrayal of an innocent girl's death seems to highlight the mixture of victimization and heroic action which acts to kindle civil pride among the youth in Kwangju. While she may seem to be simply a tragic victim, it should be remembered that she was killed returning home after donating blood - an act that may have saved the life of another. In the scene pictured below, filmed during a rehearsal, a young actress depicts Bak Geum-hui's mother crying over her death.

Her pose is likely meant to invoke this image (once again).

Breen ended his piece with this statement: "The interpretations will change over time, but that loss is forever." It would make a nice companion statement to the photo above, and I could stop writing right here. I don't think this is true, however. However laudable it may be that the tragic story of a young girl's life cut short is being used to instill pride in a new generation, it is still being used; her story is the raw material out of which an interpretation of the uprising is being constructed. I think the loss will only genuinely be felt during the lifetimes of those who were injured or lost loved ones - whether that loss remains forever will depend on the shifting interpretations of those with the power to influence the coming generations.