My latest article for the Korea Times looks at New York City artist Gregory de la Haba’s art, and his connection to the NYC landmark McSorley's Old Ale House, ahead of his exhibition opening at Hangaram Art Museum in the Seoul Arts Center (as part of the annual Design Art Fair) this weekend. The exhibition will run from May 27 to June 4, and the artist will be present during the afternoon on the opening day.

Pages

Friday, May 26, 2023

Monday, May 22, 2023

The CIA on "Political Reconstruction In South Korea" in 1980 and "Prospects for Takeover by Military Strongman Chon Doo Hwan"

The CIA Freedom of Information Act Reading Room hosts a great many FOIA CIA documents from over the decades. Some are released in their entirety, though most have sections censored. I've discovered a number of articles during the past week or two, but have likely only scratched the surface (one problem, and the reason for the use of 'likely,' is the fact that you can't easily search by the year a document was produced, only by the years they were declassified or released, which forces you to wade through a lot of unrelated material). I've discovered a number of documents related to the months leading up to the Gwangju Uprising. Two are below.

On May 9, 1980, the CIA issued an Alert Memorandum for the National Security Council titled "Growing Unrest in South Korea and Prospects for Takeover by Military Strongman Chon Doo Hwan." Though it was published before the report above, it contains much more recent information about student protests and opposition moves. As the report notes,

The Alert Memorandum is an interagency publication issued by the Director of Central Intelligence on behalf of the Intelligence Community. Its purpose is to ensure that senior policymakers are aware of impending potential developments that may have serious implications for US interests. It is not a prediction that these developments will occur. This memorandum has been coordinated at the working Level with CIA, DIA, NSA, and State/INR.

The first page, which seems to serve as an introduction, is signed by CIA Director Stansfield Turner. The following two pages contain a fuller report.

* * * * * *

Alert Memorandum: Growing Unrest in South Korea and Prospects for Takeover by Military Strongman Chon Doo Hwan

1. Current reporting indicates that the level of anti-government activities by South Korean students, supported by opposition political leaders and workers, is coming to a head. Student activists and sympathizers have enumerated a series of demands and set a deadline of 14 May for government action, failing which they threaten demonstrations in the streets. ROK authorities are reportedly devising a series of steps to forestall a confrontation, with the use of force the last resort. It appears doubtful, however, that the activists will respond to government pleas for moderation. The outcome of clashes by students and troops, if they occur, will depend on the response of several key actors, and certainly on the state of mind and the role played by military strongman Chon Doo Hwan.

2. While what we have observed of North Korean reactions to developments in the South since the Park assassination does not yet suggest an intention to exploit the situation militarily, I continue to be concerned about the adequacy of warning on Korea. In this light, the current South Korean unrest, which brings with it the possibility of a military takeover, is yet another in a series of recent events that could undermine stability in the South and tempt Pyongyang to attack.

Stansfield Turner

Alert Memorandum: Growing Unrest in South Korea and Prospects for Takeover by Military Strongman Chon Doo Hwan

A serious confrontation between ROK authorities and South Korean students is taking shape. While only a portion of the university student enrollment is involved, activists appear determined to test the permissiveness of the authorities and have put forward a series of political demands deemed unacceptable by ROK authorities, including the Lifting of martial Law by 14 May and the dismissal of top government leaders. Students in many parts of the country are planning to take to the streets and stage marches if their deadline is not met.

These developments have caused great concern among ROK officials, particularly since they are occurring at a time of labor unrest. Officials are particularly alarmed about the possibility that student and labor demonstrators will join forces in the streets. President Choi is reported to be considering a variety of measures to deal with these threats but probably lacks the will and ability to act decisively. The ROK Army Chief of Staff placed the infantry regiments of five divisions, the Special Warfare Command, and the Capital Security Command on standby alert. They are to be prepared to move into Seoul to support Martial Law Command efforts to control student demonstrators. On 6-7 May, two special forces brigades moved into the Seoul area, joining four others garrisoned there.

[3-4 lines are censored.]

The outcome of clashes between students and troops would depend upon the reactions of opposition figures, the business community, and the general public. Opposition political leaders already have expressed support for some student demands and have called for a special National Assembly session later this month to discuss the situation. Sympathy for the students among other elements, however, is limited. The majority of South Koreans probably hope that actions which might lead to instability, to a military dictatorship, and to a loss of foreign - and especially US - confidence can be avoided. It is possible, therefore, that the authorities would be able to suppress student activism without causing the confrontation to spread to other sectors of society. It is also possible, however, that such clashes -especially if they involved loss of civilian life - might bring workers and opposition political leaders into the confrontation and rupture the process of political reconstruction under way since President Park's assassination.

The attitude and role of military strongman Lt. Gen. Chon Doo Hwan with respect to these developments probably will be decisive. If, as [ 5 lines censored ]

All of the actors in this situation will, however, be very mindful of US Government attitudes. Student and opposition party leaders will be looking to the United States to restrain and inhibit crackdowns by the ROK Government and the military. Chon himself will want to avoid as much as possible provoking US reactions that could undermine his position or the US/ROK security relationship. Nevertheless, if Chon believes that the United States is out to get him and that his power within the ROK military is eroding as a result, he may be prepared to discount US attitudes in the interest of taking full control of the government.

North Korea does not currently appear to be taking any military steps in response to the deteriorating political situation in the South. However, the events of 26 October and 12 December 1979 caught the North by surprise. That is not true of the present situation. As we pointed out in SNIE 42/14.2-79, 20 December 1979, and in an Alert Memorandum, 8 February 1980, the emergence of widespread civil disorder in the South would prompt Pyongyang to consider forceful reunification of the peninsula. If Washington were seen to be preoccupied with the situation in South Asia and domestic issues, Pyongyang would probably be further emboldened by a conclusion that the US capacity to resolve the situation in the South or to defend South Korea was seriously weakened.

The ROK Army Chief of Staff placed the infantry regiments of five divisions, the Special Warfare Command, and the Capital Security Command on standby alert. They are to be prepared to move into Seoul to support Martial Law Command efforts to control student demonstrators.

If, however, there is a serious disruption of public order or widespread instability, Chun would almost certainly intervene and expand his control of the government. Indeed, the rapid retreat from tight Yusin controls and the lax enforcement of martial law and censorship over the past few months could mean that Chun is deliberately permitting the situation to deteriorate, hoping to demonstrate that the country needs a strong leader and a conservative constitution.

As we pointed out in SNIE 42/14.2-79, 20 December 1979, and in an Alert Memorandum, 8 February 1980, the emergence of widespread civil disorder in the South would prompt Pyongyang to consider forceful reunification of the peninsula. If Washington were seen to be preoccupied with the situation in South Asia and domestic issues, Pyongyang would probably be further emboldened by a conclusion that the US capacity to resolve the situation in the South or to defend South Korea was seriously weakened.

Friday, May 19, 2023

The Student Statement of May 10, 1980

Update, May 24, 2023:

The title of the statement below in Korean is "제2차 시국에 대한 공동 성명서". A full copy of the translation doesn't seem to be online but its three pages are shown on this page and the first page of it can be found on this web page (the image is located here). Many thanks to the reader who shared this with me.

Original post:

In May 1980, after student activists had achieved many of their goals for campus liberalization after Park Chung-hee's death, they began to turn their attention toward national politics, prompted in large part by Chun Doo-hwan being appointed acting director of the KCIA (while also still retaining his position as head of Defense Security Command, thereby controlling both the civilian and military intelligence organizations). The fact that Chun received this appointment just days before the 20th anniversary of the April 19, 1960 student protests that overthrew Syngman Rhee may suggest that riling the students up had been one of his goals.

On May 10, 1980, student leaders released a statement which was translated and sent in a diplomatic cable by the US Embassy to the State Department on May 16, 1980 (Telegram 80Seoul 006247, which can be found here).

* * * * * *

Subject: Text of May 10 statement by student leaders

To give Washington readers some local favor, this message conveys a rough translation of text of the May 10 statement of Seoul student leaders. Text reveals substantial traces of xenophobia and radical rhetoric. To some extent this reflects student newspeak plastered on top of the harsh tone usually employed in Korean manifestoes. However this statement was signed by student leaders from all universities in and near Seoul.

Begin text:

The Second Joint Statement on Situation.

The 26 October incident will have its historical significance only when it is regarded as an extension of the great struggle that has erupted in succession in the form of the self-immolation of Chon T'ae-il, the resistance of the settlers of Songnam City, the struggle of the workers of the Tongil Textile Factory, the farmers’ movement in Hamp’yong and, finally, the mass uprisings in Pusan and Masan.

The 26 October incident was, indeed, a great victory of the anti-fascist struggle in this land. However, it has its limit in that the masses shall not be given the victory in its real sense unless we thoroughly liquidate the accumulated irregularities through our continuous struggle, because the victory was only a result of the self-split of the dictatorship. The fact that Chon Tu-hwan and Sin Hyon-hwak, who fawned upon the Pak regime under the Yushin dictatorship, still hold power by means of controlling the comprador forces clearly shows the limit.

Therefore, the tasks remaining before us now are to repel the foreign power completely which supported the dictatorial regime in the past 20 years, liquidate the comprador bureaucrats and business groups, the hirelings of the dictatorship, who employed the methods of fictions of violence, and accomplish self-reliance in economy, correcting the dependent economic structure distorted by the remnants of the Yushin system.

Look, after the transition government of Ch'oe Kyu-ha embarked, Chon Tu-hwan and Sin Hyon-hwak and their ilk, while stressing the national security-first policy, mobilized the troops from the DMZ for the coup of 12 December, secured their political fund by raising the conversion rate and oil prices, appointed Chon Tu-hwan acting director of the KCIA, and are refusing to lift the unjustifiable emergency martial law in an attempt to realize the dual executive system and the medium-size constituency system by railroading the government proposed [draft] bill for the constitutional amendment. They are now overtly hatching the plot for maintaining the power basis of the running dogs of the Yushin system by means of the emergency martial law and the government-controlled press.

They are paying lip service that the government has no plan to introduce the double executive system and that the time schedule for democratization shall not be changed. But they still refuse to lift the unjustifiable martial law. Indeed, we cannot but suspect their ulterior intention.

Look at the pitiful [struggle] for existence of the Sabuk Coal Mine, the Tongguk Steel Mill and elsewhere. Let us look back on how our farmers have suffered and how their right to existence have been threatened under the undemocratic system of the agricultural cooperatives under the Yushin system, our national economy has at last marked a "minus growth rate” under the ruinous, dependent national economic structure. It is an inevitable outcome of the policy of economic growth by export which has protected only the interests of the comprador capitalists, totally ignoring the minimum demands of the masses.

We are united as one and uphold are banner of national struggle. We make it clear that we declared our struggle in the name of the nation and masses, and therefore, we will not withdraw even an inch.

On the emergency martial law: the entire masses demand lifting of, the emergency martial law. They clearly know that the logic of the national security by the remnants of the Yushin system is fictitious and is a lie aimed at maintaining their power. Their "national security" is not for the nation but for the continuation of the Yushin system and for its comprador forces. In other words, their "national security" is for the protection of all the anti-nationalist forces. Their emergency martial law is not for the national security but for the suppression of the masses. It is the cold water to cool the masses’ zeal for democracy, and therefore, is detrimental to the genuine national security. If the current situation is as serious as they claim and, therefore, the martial law cannot be lifted, how can you explain the Ch'oe Kyu-ha's recent visit to the Middle East? How can a head of state leave his country if the situation at home is so grave? We are convinced that there is no reason whatsoever for continuing the martial law, and we cannot but suspect that Ch'oe's visit to the Middle East is aimed at abetting a coup by Chon Tu-hwan.

On government-initiated draft of constitutional amendment and the double executive system: The so-called "eclectic type" double executive system is a scheme hatched by Sin Hyon-hwak and Chon Tu-hwan, the running dogs of the Yushin system, in the self-contradiction of political development under the martial law. The double executive system is basically an expression of their sense of crisis that they, the remnants of the Yushin system, cannot seize power through direct and popular presidential elections. According to this system, the president shall be in charge of foreign relations and national security, while the head of the cabinet shall be in charge of home affairs, and in case of an emergency, the president shall hold the total power. Under this system, a president who alone is in charge of foreign relations and national security can suppress the masses' demand for the rights of existence under the excuse of national security and prevention of social disorder. This system is designed to justify the military intervention in the national politics and pave the way for military strongmen to wield power in handling state affairs under the pretext of pseudo national security...

On the other hand, the medium-size constituency system is a system under which candidates need enormous amounts of money and runner-ups can also be elected to the national assembly.

The Yushin clique hatching a big plot now to maintain their power is composed of a handful of the Yushin remnants within the military including Chon Tu-hwan who are utilizing the military for political purposes, concealing the zeal of the majority of soldiers for democratization, and some bureaucrats including Sin Hyon-hwak who have fawned upon the Yushin system.

They are now trying to realize the double executive system and the medium-size constitutency [sic] system against the wishes of the majority of the masses, controlling the press, holding public hearings of the government's amendment deliberation committee, and fabricating public opinions. For this, they are maintaining the emergency martial law and are supressing [sic] the masses' indignation.

On the press: the press tycoons who forcibly drove to the street the reporters of the Tong-A Ilbo and the Choson Ilbo who struggled for their rights, haven't cast off their habit of parasites and are still serving the running dogs of the Yushin system. They are distorting the true picture of the just struggle of the Sabuk workers by describing it as "riot by rebels" and "a lawless world", etc. They reported the campus democratization movement and the demonstration against the military training at army bases as "violence" and "riot" and even "acts of those who have nothing else to do".

Of late, they report the students' movement quite in detail, using such words as "peaceful" and "pure", etc.. However, if theirs is the simple logic that the students' movement is peaceful and understandable only because it is limited to on-campus movements, they will surely report it as "creating social disturbance" and "not peaceful" if we take to the street to expand the arena of our struggle.

Men of the press, don't you think the entire press should have joined in the sit-in struggle at the Chungang Ilbo (newspaper) company which was staged in protest against the recent police assault on reporters in Sabuk? Don't you think it is now time for the press to formally demand the lifting of the martial law and regain your rights? The entire masses will extend their full support for the struggle of the press. At the same time, you should strongly demand the re-employment of the dismissed reporters.

We affirm that our struggle is vital to attaining a country in which the masses are its true masters, a country unified on the basis of the masses. We firmly believe that our struggle is not only for us but is linked with the struggle for survival of the working masses, and we will not lower in vain our banner which we have raised high.

We will further intensify our struggle in the name of the masses and will sublimate it to the rising of the entire collegians to achieve this national task.

- Lift the emergency martial law.

- Out with Chon Tu-hwan and other political soldiers.

- Out with [PM] Sin Hyon-hwak and other Yushin remnants.

- Release [poet] Kim Chi-ha and other conscientious offenders.

- Dissolve Yujong-hoe* and stop government-initiated drafting of constitutional amendment.

- Dissolve the national council of unification.**

- Release the hundreds of students who are imprisoned in connection with the democratization movement.

- Guarantee the three labor rights, abolish the national security defense law and other evil laws, and release the imprisoned workers.

- Democratize the agricultural cooperative associations and guarantee the farmers' rights.

- Press tycoons should stop breaking faith and support the reporters' struggle for the free press.

On possible school closure: we firmly believe that the peaceful democratization movement of the collegians, demanding reforms in the "order of violence" which has suppressed the people's right to live and corrupted the righteous spirit and conscience of the nation, is the expression of our national consensus. We have not forgotten even for a moment either our zeal for study in the course of expressing our opinions. Therefore, if the campus is ordered to close down, we shall regard it as a blatant attempt to suppress our peaceful and just demands. We want to make it clear therefore that we will hold the Yushin running dogs, including Chon Tu-hwan and Sin Hyon-hwak, who have become the mark of national criticism, entirely responsible for the consequences arising from it. If it becomes impossible for us to hold on-campus meetings, we shall hold meetings outside the campus to proclaim far and wide the injustice of the oppressive regime and the justice of our demands. We therefore expect the rational judgment of the responsible authorities and hereby proclaim our resolutions as follows:

- We reject orders of campus close-down.

- We will stage peaceful on-campus demonstrations in principle for the time being.

- If and when campus close-down is ordered, we will hold separate demonstrations at six p.m. on the first day of the close-down at the following places: Yongdungp'o Intersection in Kangnam, Kongdok-dong rotary in Kangbuk area, Ch'ongyangni rotary and in front of the Seoul Stadium in Kangdong area.

- We urge all the conscientious students of colleges, junior colleges and universities in Seoul and provincial cities to join us in our decisions.

General student councils of Kon Guk University, Kungmin University, Toksong Women's College, Industrial College, Seoul National University, Songgyun'gwan University, Sungmyong Women's University, Yonsei University, Ehwa Women's University, Hanguk Theological Seminary, Hongik University, Korea University, Tan Guk University, Tongguk University, Sogang Jesuit University, Seoul Women's College, Songs In Women's College, Sungjon University, The Han Guk University Of Foreign Studies, Chung Ang University, Hanyang University, and Taeyu Junior College of Engineering.

End text.

Gleysteen

* * * * * *

* The Yujeong-hoe was the one-third of the National Assembly appointed by Park Chung-hee under the Yushin Constitution, which allowed his loyalists to control that body even if the opposition won a majority in elections.

** The national council of unification was the appointed body tasked with electing the president.

Near the beginning, the statement speaks of the need to "repel the foreign power completely which supported the dictatorial regime in the past 20 years". This kind of rhetoric is worth remembering when it's argued that anti-Americanism began in Korea after the Gwangju Uprising. (I've noted before that Park allowed anti-American protests by students in 1968 in order to pressure the US.) As well, though I haven't read this in Korean, I'd bet the term for "foreign power" (to be repelled) is 외세, a term which usually connoted Japan, but which was used not only by the students, but by Park Chung-hee's government as well to obliquely refer to the US when criticizing it.

[Update: It is indeed 외세. That sentence in Korean reads "그리므로 10.26은 또한 20년간의 독재를 가능케했던 외세의 완전한 배격, 그 하수인으로써 폭력적 대중 수탈에 근거한 매판관료와 재벌의 철저한 해퇴, 그리고 이 매판적 유신잔당들에 의해 왜곡되어진 종속적 경제구조의 자립화를 우리에게 다시금 과제로써 남겨놓고 있는 것이다."]

It's also interesting how the statement leverages the memory of Cheon Tae-il and the Gwangju (Gyeonggi-do) settlers' uprising (events from 1970 and 1971) and the Donga Ilbo struggle of 1974-75 to create a genealogy of resistance to Park Chung-hee.

The "double executive system" referred to is explained in a May 14, 1980 CIA report titled "Political Reconstruction In South Korea: A Difficult Road":

Although popular sentiment appears to favor direct, popular election of the president, many--including President Choi himself--would prefer an indirect election by the National Assembly. This would ensure the election of a conservative candidate acceptable to the military. [...] An alternative would be to institute a "dual executive" system with a relatively weak president and a strong Prime Minister.

The combination of a volatile political atmosphere and an ambitious, conservative military leadership appears to be driving South Korea toward more turmoil. The students, disgruntled workers, and others who are criticizing the interim government and the military most loudly seem to be playing into Chun's hands. Their recent call for an immediate end to martial law could provoke the kind of instability that Chun needs to step in. [...]If a confrontation between students and the military can be avoided, the government has a better than even chance of sticking to its transition schedule, which calls for constitutional revision later this year and presidential elections next summer. If a confrontation develops, the entire transition process will be slowed; it is an open question when or whether Chun Doo Hwan would relinquish the authority he would acquire from the resulting turmoil.

The full report - which I'll post soon along with another - does not come across as very positive about the prospects of Chun relinquishing power should he gain it, and in fact offers this: "the rapid retreat from tight Yusin controls and the lax enforcement of martial law and censorship over the past few months could mean that Chun is deliberately permitting the situation to deteriorate, hoping to demonstrate that the country needs a strong leader and a conservative constitution."

The Student declaration posted above was released on May 10, when students were still demonstrating on campuses. These student on-campus rallies were disrupted on May 12 by rumors that North Korea might attack and the ROK military might move onto campuses. Student leaders called the rallies off, but by the next day they realized they had been fooled by these rumors, which they assumed had been spread by the military. This angered even the moderate students and gave the upper hand to the radicals who urged that protests move into the streets, which they did, in historically large numbers, on May 14 and May 15.

These protests were used as a pretext for the military takeover of May 17, (though it may also have been influenced by the fact that not just the political opposition but also former ruling party politicians like Kim Jong-pil announced their openness to the student demand that Martial Law be lifted, and a National Assembly session was just days away), and it's hard not to notice the fact that it was rumors of a DPRK attack that students attributed to the military that ultimately led to large scale protests off campus. It's not known if this was a deliberate attempt to foment unrest by the military or not... perhaps some day we will find out.

There is a record of how one key member of the military group felt about student rhetoric. In his meeting with Martial Law Commander Lee Hui-seong on May 18 when he asked for an explanation of why martial law had been expanded, US Ambassador Gleysteen reported Lee’s comments about the students:

On studying the students' statement issued following the meeting at Koryo University, he had become concerned over the communist terminology. The statement urged class struggle, denounced the capitalist system, supported communist themes, and called for a mass uprising of the people. In amplification or this point, General Lee said that students who had initially refused military training but later reconsidered had been taken to the Third Military Academy. Several statements heard from these students caused serious concern. One said that while Vietnam had changed its system and might not have achieved democracy, at least the country had been unified. Another student had suggested modification in the ROK to a system between the present one here and that in the north to achieve unification. Another student had questioned ROK support for U.S. and Japanese capitalists. When asked where they had learned such things, 50 percent of the students said from older students and 20 percent said from the societies and clubs on their campuses. These were students with only two months of university and he was very concerned over this type of thinking taking hold so quickly on the nation's campuses. If it were not controlled, Lee feared the ROK would be communized in a manner similar to Vietnam.

While Lee’s attitudes were dismissed by Gleysteen as “pure Yushin thinking,” they were clearly shared by the generals who had met the previous morning and decided a takeover of the country by the military was necessary. How the ROK's cabinet felt about this when they met to "discuss" the expansion of martial law on the evening of May 17 was immaterial, according to a Defense Intelligence Agency report:

From the time they left their car in front of the main capital building, moved through security and then up to the conference room, received an explanation as to what was wanted, given an opportunity to sign the document which was prepared and awaiting signature, and returned to the car was approximately 20 minutes. Source observed that, in order to get to the conference room being used, participants had to use hallways lined with armed soldiers. Source felt this had an overly ominous effect on the proceedings. It was apparent a few of the ministers were fearful that they might be arrested. At least one expressed such fears privately after the experience was over. This report reflects the strong handed way the army and the PM [Prime Minister] handled the meeting at which total ML [Martial Law] was approved.

All attempts at holding demonstrations over the next few days were immediately pounced on by troops or police and stopped before they could happen, except in Gwangju.

Thursday, May 18, 2023

The Gwangju Uprising after 43 years

Today marks the 43rd anniversary of the beginning of the Gwangju Uprising.

An index of my posts over the years about the uprising can be found here.

I've spent time over the past few years reading through US diplomatic cables from a variety of sources (which appear in this bibliography, which I've just updated). Interestingly, many of the cables which had parts redacted that have been more recently released in unredacted form turn out to have not been censoring material that made the US look bad - they were censoring material that was critical of their ally or that might make prominent Koreans look bad (three of these people became president of the ROK in the 1990s).

The cables actually provide fascinating windows into what was happening in Korea at that time, and I'll post, over the next week, some of the more interesting ones I've found, such as a May 1980 Student manifesto.

Also worth noting is that a new book has been released:

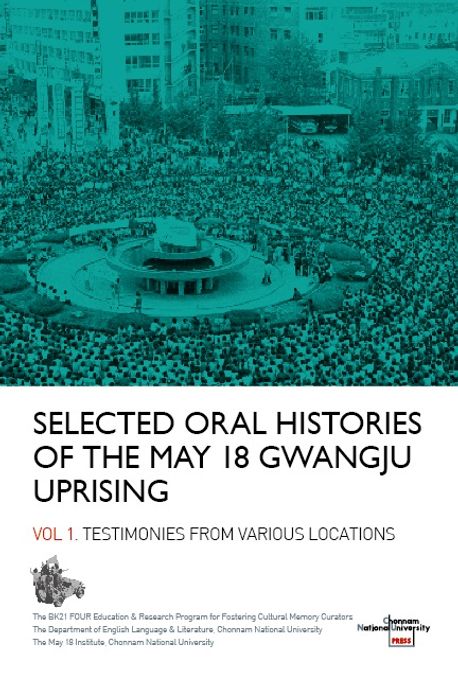

Kim Yeon-min, Robert Grotjohn, eds, Selected Oral Histories of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising: Vol. 1. Testimonies from Various Locations, Chonnam National University Press, 2023.

The Hankyoreh also reported on disturbing findings by the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission: Martial law forces continued killing Gwangju citizens after suppression operation, says eyewitness

The May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission's chairperson was also recently interviewed by Tim Shorrock, and there is some interesting material there. The chairperson noted that requests have been made to the US for military and CIA documents (State Department and Carter Library documents were released in 2021) and that they may be able to disprove claims by Chun's group, while Shorrock implies they could shed light on the "dark alley that investigators call 'the Fort Benning connection' – that is, the close relationship between Chun and his accomplices with American generals and special forces operatives in Korea." The article does little to shed any light on this, however, merely pointing out a handful of references to American officers who interacted with the ROK military as part of their duties and implying newly-declassified materials may implicate them.

In the aftermath of the “12/12 Incident,” U.S. embassy, military, and State Department officials claimed that Chun [Doo-hwan] was an obscure general little known to US Forces Korea, and said they had been assured at the highest levels it would never happen again. But those claims were untrue, according to James V. Young, who was the military intelligence adviser to U.S. Ambassador William Gleysteen at the time.

Skipping over the fact that Young was the assistant defense attache, the last sentence implies that Young’s revelations (in his 2003 memoir Eye on Korea) reveal that U.S. embassy, military, and State Department officials were lying, whereas Young actually wrote that prior to 12.12, “I began to wonder whether the left hand knew what the right hand was doing—obviously we were in big trouble if Washington had such a superficial understanding of the situation that it did not know who Chun was, especially after all the reporting we had done. The problem was that, while the DIA and CIA obviously had large amounts of information, the State Department, at least at the working levels, was only peripherally aware of this important personality.” [Page 63] Rather than lies, Young points to bureaucracies with differing priorities at work, hence Chun Doo-hwan being "little known" to the State Department.

As well, we're told that

Young wrote that Chun was especially close to Col. Donald Hiebert, a U.S. Army Special Forces soldier who was the U.S. embassy’s defense attache in 1980. Hiebert first met Chun in the 1970s. At that time, “One of [Hiebert’s] frequent associates was a young colonel, Chun Doo Hwan,” Young wrote. “Hiebert had met the colonel in Vietnam, where Chun had commanded a battalion, and had continued their association in Korea. They met rather frequently.” Young said he met Chun for the first time at the U.S. ambassador’s residence in 1972 and several times after that, “usually accompanied by Col. Hiebert.”

The problem with this paragraph is that there's an error in it that renders it pointless: Hiebert was the U.S. embassy’s defense attache in 1972, not 1980. The Vietnam War-era NYT article about the ROK military in Vietnam that is linked to is interesting enough, I suppose, but Hiebert had nothing to do with the events of 1979-1980.

That said, Shorrock is always able to dig up fascinating material, like this interaction between North Koreans and Americans in early June 1980 about the Gwangju Uprising.

Hopefully the US will release the military and CIA records that have been requested, particularly because they provide such an interesting window into that time period; the Embassy cables, for example, feature accounts of meetings with the president, his secretary, military leaders, politicians like Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung, dissidents, and more. I only recently started digging into the FIOA declassified CIA reports, searchable here (though not very conveniently). Some I will post soon, while others, like this one, provide a list of cables (titles, dates, recipients) from 1979-1980 turned over by General Wickham when he retired for declassification review.

Needless to say, there will always be more to uncover about the events of 1979-1980.

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Leading an RAS excursion to Jeong-dong this Saturday

This Saturday, May 20, at 1pm I’ll be leading a Royal Asiatic Society excursion to Jeong-dong, the historic area behind Deoksu Palace, where missionary schools, churches, and Western Embassies can be found. There I’ll tell the stories of how Americans, Canadians, British, and others took part in Korea’s history between 1883 and 1945, a period of initial contact, wars, and resistance to Japanese imperialism.

On this excursion we’ll visit sites such as the former National Assembly, the Anglican cathedral, the Salvation Army, Ewha Girl’s High School, Jungmyeongjeon Hall, the former sites of the Russian Legation, the Sontag Hotel, and the Baejae Hakdang, as well as the Jeong-dong First Methodist Church and the Seoul Museum of Art, which is housed in the colonial era-built former Korean Supreme Court building. We will also observe various dilapidated or vanished buildings and paths that are currently being restored and discuss the preservation of the past in Jeong-dong.

For more information or to make a reservation, please look here.

Wednesday, May 03, 2023

Sundown (or when Koreans covered Gordon Lightfoot)

I was sorry to hear of Gordon Lightfoot's passing - his music was certainly part of my childhood, and I know my parents saw him play live back in the early 70s and in 1989. At one point circa 1983 or 1984 the only tape player my family had was in the car, and we didn't have that many tapes yet, so a Gordon Lightfoot collection with 'Did she mention my name' and 'In the early morning rain' got played a lot, which is a good thing.

Many years ago I was given an mp3 of a Korean cover of his song "Sundown," but because it had the wrong singers in the filename, I could never find any information about it. It was only in the last year or so I realized that it was by Seok Chan, from his first full length album released in 1974. Unfortunately, it's not clear when in 1974 it was released (Lightfoot's song was released in late March 1974), but we can be sure that, with Sundown going to number 1 in the US, it got played on AFKN, heard by Koreans, and within 9 months this cover version had been recorded and released.

(By the way, a useful term when looking for Korean-language covers of Western songs is 번안곡.)

My favourite cover of Lightfoot's music is also my favourite song by The Unintended (off of an EP of Lightfoot covers):

And while we're at it, here's a 1971 hour-long concert by Gordon Lightfoot (broadcast by the BBC in 1972).

Thanks for the music, and rest in peace.