Part 2: In Seoul and Chemulpo

By February 1, 1904, Frederick McKenzie had arrived in Seoul and experienced his first impressions of the city.

Placed in a fertile, undulating valley, watered by a never failing stream, guarded by great lines of hills, with a climate at once bracing, temperate, and delightful, Seoul should be the crown of Asia. […] To judge Seoul entirely from a western standpoint is scarce to do it justice. At first one finds little save to condemn. From the hungry dogs that rake out the infant corpses and eat them on suburban burying-grounds, to the corrupt officials who have fattened off oppression in the many royal palaces for so long, all excites repulsion. The cowardice of the men, the subdued and half-concealed women, the hovels that shelter most of the people, the open and malodorous drainage, the dirt, the sordidness, the poverty, chill a stranger.Describing Seoul as “a powder mine”, he said the foreigners there were afraid of a Boxer-style uprising, and that “few of us went abroad without seeing that our revolvers were ready in our hip pockets." The reason for this was explained by Lieutenant E.T. Witherspoon, who was commanding the Marine Guard at the U.S. legation in Seoul at the time. On January 14, 1904, he wrote

Seoul is, in truth, a strange combination of barbarism and modernity, of reform and of the grossest tyranny, of repulsion and of attraction.[…] Conjure up a city where the men ride on electric tramways, and the better class women are never allowed to walk the street or to show their faces in public; where the mayor is chosen because of his skill as a sorcerer, and where he uses the ordinary newest pattern Swedish telephone to help him transact business with his colleagues; where the king sits under the rays of an incandescent light while deciding the number of devils that shall be displayed, and magicians engaged, for his mother’s funeral. That is Seoul. [...] It was my good fortune to see the city in the last days before the Japanese secured a controlling voice in administration.

The situation here is a little more serious today, as the Corean newspaper yesterday came out with a very inflammatory article, calling on the people to murder all the foreigners, and mentioning us first. On account of the street railroad having killed one or two children, they have a special hatred for Americans. It is now a foregone conclusion that the railroad and its property will be the first place attacked.

U.S. Minister Horace Allen requested that the rest of the marines be sent from Chemulpo to Seoul to protect the Seoul Electric Co. plant.

In his report to his superiors the next day, commander William Marshall of the U.S.S. Vicksburg, which was then moored in Chemulpo harbor, said that he had sent the troops and that there were, at that point, 800 foreign troops in Seoul; half were Japanese, 200 were Russian, 97 were American, and the rest were French, English, or Italian. As Witherspoon explains, an incident took place on January 24:

About 9:30 A.M., a trolley car just outside the south gate ran into a rickshaw man and killed him instantly, crushing him to death. The man ran, (or was pushed), directly in front of the car, so that it was not the fault of the motor-man at all, and the accident could not have been avoided as far as he was concerned. A mob immediately assaulted the car, overturned it, and dragged the motorman to the South Gate railway station, where they were beating him to death when our men rescued him. There is a guard of Corean soldiers at the gate who stood there and watched the whole proceedings, making no attempt to interfere. [...] I am inclined to think that the unfortunate ricksha man was deliberately pushed in front of the car by some of these people who are waiting for the first opportunity to get up a riot. Dr. Allen thinks so, too [...] The affair shows the Coreans what our men are here for, and may prove to be a very good thing. Dr. Allen thinks that, if our men had not been here, a general riot would have followed, with, possibly, a great deal of bloodshed.McKenzie was not the only foreign reporter in Seoul. Besides Japanese reporters, there was, as Witherspoon described him,

a reporter here who is giving us more or less trouble…named Kingsley who, a short time ago, in Tokio, made a very bitter personal attack on Minister Griscom. He has come here under an assumed name, as a war correspondent for the London Mail. [...W]e decided to simply ignore him, in consequence of which, he has cabled to his paper the most outrageous falsehoods about the men, stating that they are all drunk, and going around the streets looking for a fight, and are wholly lacking in discipline. [...] He goes out with our men and tries to get them drunk in hopes of getting information.McKenzie, along with an interpreter, met Yi Yong-ik, the “supreme minister” of Korea, who was in charge of the military and the public purse, and Yi asked him his opinion about whether war would come.

Yi Yong-ik (from here)

Yi Yong-ik (from here)Yi spoke emphatically. “We believe there will be peace,” he said. There were be no war.” I gazed at him. Did he not know that but an hour before the Korean wires had been cut at Masampho [Masan] by Japanese troops landing there? Was he unaware that at this moment Japanese transports were stealing up from Tsushima, full of armed men, and that Russian transports were filling with soldiers at Port Arthur? I urged such points on him.The Russian minister to Korea Pavloff had also felt that war would not come, saying, "There will be no war. Even if there were, all that would happen could be that the Japanese would lose their fleet and then would have excuse for suing for peace."

“But what matter these things to us? Let Russia and Japan fight; Korea will take no share in the fighting. Our Emperor had issued his declaration of neutrality. […T]here will be no need to appeal to the Powers if our neutrality is broken. They will come without being asked, and will protect us.”

Here Yi stood. He resorted to his old and well-known trick of shutting his eyes to unpleasant facts.

“The Emperor must grieve over the trouble in the East,” I remarked.

“Why should he grieve? It is not our people who are quarreling. If war did come, it would not concern us. Our Emperor does not grieve.”

McKenzie found it hard to know what might happen, as he explains:

We, in Seoul, knew less of the details of the diplomatic struggle than people in Europe or America. […] The telegraph wires from Fusan and Japan had conveniently broken down. The northern wire from China was not in working order. A strange paralysis seemed to have lain hold of merchant shipping, and the anxious faces of the ministers told us that the worst was now inevitable.Waiting at Chemulpo was Robert Dunn, who took several photos of the landings.

On Monday afternoon I was riding to the legations when a messenger ran up to me with word from my man at Chemulpo, that a strong Japanese fleet had appeared in the bay with many transports and warships. It did not take long to get first to the cable office and then down by rail to Chemulpo. Here a wonderful scene presented itself.

It was already dark. The streets were covered with snow, and the harbour had much floating ice. All along the front of the town log fires were lighted at short intervals […] and revealed the dark lines of landing boats in the water, full of troops, and long columns of soldiers already standing at attention on the shore.

McKenzie continues:

That afternoon, the Russians, alarmed by the non-arrival of dispatches, had sent out the gunboat Korietz to make its way to Port Arthur. It left at ten past three, and at four o’clock the people on the shore saw it returning with a Japanese fleet behind and around it. […] The two Russian warships were caught like rats in a trap. All night long they had lain still, watching the movements of the Japanese troops, yet not daring to strike.[…]According to the captain of the USS Vicksburg, William A. Marshall,

Part of the Japanese force, consisting of four cruisers, six torpedo boats, and destroyers convoying three transports, came to anchor here shortly after 5 o'clock [...] Disembarkation of soldiers was at once begun and by midnight three thousand men had been landed, fifteen hundred taking possession of Chemulpo and the others going to Seoul.At 7:00 the next morning, Tuesday, February 9th, the Japanese Admiral sent formal notice to the Russian commander announcing a state of war, and declaring that if the Russian vessels did not leave the harbour by noon, the Japanese would attack them at 4:00.

The Russian captain met with the English, French and Italian (but not American) captains of the foreign ships in the harbor, but they refused to get involved, though they did send a formal protest to the Japanese against them attacking in the harbor.

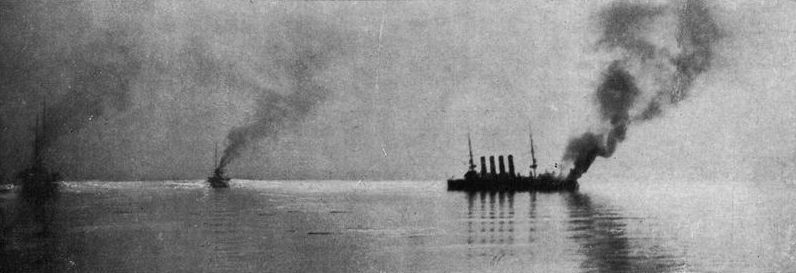

Both Russian ships, after throwing all burnable wooden items overboard, sailed out of the harbor before the noon deadline, and were fired on by the Japanese at 11:50.

The Russians maneuvered rapidly to avoid the fire, but five shells struck the Variag in rapid succession [. One shell] demolished the fore-bridge and set fire to the debris, compelling the Variag to cease firing for nearly five minutes while the crew went to the fire station. The bridge was torn to ribbons, as though it were paper, by a shell.Also watching the battle was Robert Dunn, who was on board the USS Vicksburg in the harbor, and who took several photos.

McKenzie continues:

For the first time the new Japanese explosive, shimose, was brought into play. Its effects were amazing. The shells split and burst into innumerable minute fragments [.] One wounded man, alone, was afterwards found in the hospital to have over a hundred separate pieces of shell in him. The shell bursting on the ships side drilled myriad holes in the steel, as though a machine gun had played at close quarters on wood. Both bridges were wrecked, and the third funnel was shattered. The scene on board was indescribable. The ship was a living hell. [...]The Russian ships managed to turn around and return to the harbor, making it to safety at 12:40, when the foreign ships immediately dispatched surgeons and medical supplies. The battle lasted 50 minutes. On the Variag 33 men were killed and 97 were wounded out of a crew of 580. The Japanese suffered no casualties on their warships.

The noise of the shot hitting the sides of the ship, the unceasing tearing of the shells through the air, the bursting of explosives on board the ship, the fires breaking out in various parts, all added to the horror. […] One Russian lieutenant describing it to me a few hours afterward, summed it up. “There was blood, blood everywhere,” he said, “severed limbs, torn bodies. Here was a head, there lay a leg, not far away my comrade of yesterday was now ripped in two. The smell of blood pervaded all.”

The Japanese now left the vessels alone, and the captain of the Variag prepared to destroy the ships. The men were accordingly removed to the foreign vessels. […] At 4:00, to the minute, the Korietz was blown up.

The burning Variag slowly began to sink after members of her crew opened the valves in the engine and fire rooms, and it rolled over and sank at 6 pm, while the Russian mail boat Sungari caught fire as well, “and for many hours, until past midnight, she lit up the harbor with her glow.”

Mckenzie's notes his reaction to the battle:

For myself, as I turned into the club house on the hill top, I felt sore at heart. The allies of my own country had won, but brave men had fallen, and for the moment the thought of their mortification blotted out all feelings of jubilation.Most of the photos of the battle above were taken from the U.S.S. Vicksburg, but not by Dunn (more photos, as well as dozens of letters and documents, can be found in the collection of the captain here). This book relates the story of the other photographer:

There was a Lieutenant on the U. S. gunboat Vicksburg, from which some of Mr. Dunn's photographs were taken, who managed to get a small snap-shot of the blowing up of the Korietz. Mr. Dunn heard of this and offered the Lieutenant $100.00 for the use of the film to make a print for Collier's. The officer declined and took the film to a Japanese photographer on shore to be developed. The next day the Jap explained, with a melancholy face, that the light must have struck the film, for it had not come out in the developing.Those in Seoul did not just hear word of the battle; Witherspoon wrote later on the ninth that, "We have been listening to the sounds of the fight and heard all the heavy guns, and you can imagine the excitement up here." Speaking of the Japanese troops that were landed, he said “600…arrived here this morning, and the others are expected during the afternoon. The later arrivals are expected to occupy the hills, the troops this morning going to the Japanese barracks here in the city.”

"Two days later," wrote Mr. Dunn, "the young Lieutenant was offered a print of the sinking of the Korietz for the sum of twenty sen ten cents by the Japanese photographer to whom he took his film. The print was strangely familiar. It was the size of his film, the identical view he had seen in his finder. It was his view. He proceeded to lay down the law to the photographer, but the imperturbable Oriental only repeated that he was very sorry. The officer must be mistaken; he was very sorry. The officer was more than sorry. He swore for a short space. Then he went and found a policeman. He had the photographer arrested for theft, which was a mistake, for it gave the wardroom of the Vicksburg much munition for jests at his expense. There was a trial, an all too public trial. All the friends of the officer went, for it was great fun. The photographer swore it was not the film of the naval man from which he made the print; that film had been spoiled. He was very sorry. It might be that an employee had stolen the film and placed a fogged one in its place. Yes, that might be true; perhaps it was. He was very sorry. He could not find that employee. He had gone north with the army. He was very sorry. Finally the naval man was awarded damages totaling fifty yen twenty-five dollars. He had to spend that in refreshments for the laugh was on him. In his cabin some one had posted the legend: ' A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.' "

Dunn took several photos of the Japanese troops being landed every day at Chemulpo:

He also followed them into Seoul...

This was likely taken near what is now Gongdeok station, where an

This was likely taken near what is now Gongdeok station, where anincomplete Gyeong-Ui line met the Seodaemun-Mapo streetcar.

...where he photographed them marching in the streets near Namdaemun and Namdaemun (now Seoul) Station.

It was at Namdaemun Station on February 12 that Russian Minister Pavlov and the other members of the Russian legation, accompanied by their marine guards, were escorted by the Japanese to take a train to Chemulpo. Many in the foreign community came to see them off.

As McKenzie describes it,

At Chemulpo the scene was much the same. There was a line of Japanese guards from ship to boat. Craft were waiting to take soldiers and refugees to the French warship Pascal ready to receive them, and last of all there was a launch for the minister and his party. They would not hurry. They had a word for every one, a laugh, a joke, a reminiscence for all old friends. None was more gay than the Minister's wife. And yet when at last she got on her launch and turned for a final farewell, it took no special vision to see tears welling in those eyes.

McKenzie and Dunn were both present at Chemulpo to record the departure of the Russians. Had they been able to contact their fellow correspondents in Tokyo, those in both locations might have asked a question: What had happened to Jack London?

This is very interesting. I'm actually in search of private papers and especially photographs taken by or of Frederick McKenzie. Do you know where these might be found (other than those published in his books?) Any assistance on that would be very helpful. I'm in the process of contacting the archives of the Daily Mail and the Canadian national archives but the process is rather slow...

ReplyDeleteI'd be very curious to find his photos or papers as well, but there's little that I know about him (other than his books, many of which are available at archive.org).

ReplyDeleteI think a lot of his biography that I'm aware of is in my first post of this series. A few things not mentioned - the 1969 Yonsei University Press edition of Korea's Fight For Freedom has a photo of McKenzie provided by the 'Chicago Historical Society.' McKenzie also worked for the Chicago Daily News from 1921 (and the Times (of London, I presume) as its Berlin correspondent until 1914).

I'm curious - why are you interested in McKenzie? As a Canadian, I find it interesting that he wrote a book about Vimy Ridge decades before Pierre Berton, but history seems to have forgotten McKenzie, except perhaps in Korea, where his photo of the righteous army at least is well known.