James Creelman, in his report on the battle of Pyongyang, which took place on September 15, 1894 during the first Sino-Japanese War, tells us about the actions of the Chinese army in the city before the battle and their effect upon the city's inhabitants:

In forty-two days the Chinese army built more than thirty earthworks outside the walls of Ping Yang. There were miles of new fortifications. [...] As the Japanese army moved forward to the rescue, the Chinese generals made merry with the dancing girls of Ping Yang, renowned throughout Asia for their grace and beauty. All was pomp by day and revelry by night. The Chinese soldiers broke into the houses of timid Coreans, and treated their wives and daughters shamefully. Drunkenness and debauchery ran riot, and while the generals caroused with the dancing girls, the whole city was looted. Hell seemed to be let loose. The frightened inhabitants fled to the fields and forests -- men, women, and children -- and remained there until the Japanese army entered the city, when they crept back, many of them dying from starvation and exposure.Even allowing Creelman his penchant for slight exaggeration, it should be noted, however, that he never actually stayed to see the city's inhabitants return, or the behaviour of the Japanese army after it triumphantly entered the city. Isabella Bird Bishop, on the other hand, in her book Korea and Her Neighbours, described Pyongyang during her visit there in November 1895, more than a year after the battle, as

a prosperous city of 80,000 inhabitants reduced to decay, and 15,000 - four-fifths of its houses destroyed, streets and alleys choked with ruins[...] Everywhere there were the same scenes, miles of them[...]After reading this, I had wondered if there was a connection between the incredible growth of Pyongyang's Christian population and the destruction the city experienced during the Sino-Japanese war. This description of early missionaries in Pyongyang, from Donald N. Clark's Living Dangerously in Korea: The Western Experience 1900-1950, makes no mention of the war, however:

Phyongyang was not taken by assault; there was no actual fighting in the city[...] When the Japanese entered and found that the larger part of the population had fled, the soldiers tore out the posts and woodwork, and often used the roofs also for fuel, or lighted fires on house floors, leaving them burning, when the houses took fire and perished. They looted property left by the fugitives during three weeks after the battle... Under these circumstances the prosperity of the most prosperous city in Korea was destroyed.

The story of P'yôngyang as a missionary station began in 1890, when the newly arrived Samuel A. Moffett paid a two-week visit to investigate the possibility of opening evangelistic work there. The following spring, Moffett and his colleague James Scarth Gale visited P'yôngyang again while on a three-month exploratory journey by foot and horseback. They held services in the city but found that people were still "suspicious of foreigners and afraid of Christian books" because of the government's recently lifted prohibition against Christianity. P'yôngyang remained impenetrable for several years, receiving occasional visits from Seoul-based missionaries who invariably found the local authorities inhospitable. The Presbyterian Mission assigned Samuel Moffett to P'yôngyang as a full-time missionary in November 1893, and, after a rocky beginning that included attempts on his life by neighbors intent on killing the "foreign devil," he succeeded in buying property and founding a proper mission station in January 1895.A somewhat humourous description of the difficulties in starting missionary work can be found in Elizabeth A. McCully's book A Corn of Wheat (quoted from in Times Past in Korea: An Illustrated Collection of Encounters, Customs and Daily Life Recorded by Foreign Visitors), from which this January 17, 1894 entry is taken:

After seven days' journey I reached Phong Yang, and went at once to one of the houses which had been purchased for our use, but which, on account of the opposition of the governor, we were unable to occupy for several months. It had been used as a home for dancing girls, and was still being used for the same purpose. After some difficulty they consented to give up the house. The following two nights the house was vigorously stoned by a band of men who had been accustomed to spend their evenings there, but had now been defeated in their evil purposes.The aforementioned Samuel Moffett was Isabella Bird Bishop's guide in Pyongyang (she mentions that the Japanese troops looting the city helped themselves to $700 worth of his possessions). She describes the efforts taken to find him during her visit in November 1895:

Taking a most diverting boy as my guide, I went outside the city wall, through some farming country to a Korean house in a very tumble-to-pieces compound, which he insisted was the dwelling of the American missionaries; but I found only a Korean family and their were no traces of foreign occupation[.] Nothing daunted, the boy pulled me through a smaller compound, opened a door, and pushed me into what was manifestly posing as a foreign room[.]

I had reached the right place. It was a very rough Korean room, about the length and width of a N.W. Railway saloon carriage. It had three camp-beds, three chairs, a trunk for a table, and a few books and writing materials, as well as a few articles of male apparel hanging on the mud walls.

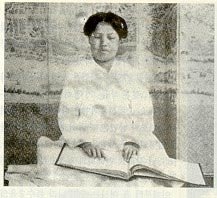

William James Hall and Rosetta Sherwood Hall's House where

William James Hall and Rosetta Sherwood Hall's House wherethey carried out their medical and missionary work.

Upon meeting Mr. Moffett, he described the post-battle scene in the Pyongyang area

as one of 'indescribable horror'. [Three weeks after the battle] there were 'mounds' of men and horses stiffened in the death agony, many having tried vainly to extricate themselves from the pile above them. There were blackened corpses in hundreds lying along the Peking road, ditches filled up with bodies of men and animals[...] Even in my walks over the battlefield, though the grain of another year had ripened upon it, I saw human skulls, spines with ribs, spines with the pelvis attached, arms and hands, hats, belts, and scabbards.Such a description is not surprising, as it echoes James Creelman's report on the immediate aftermath of the battle:

The scene was horrible beyond words to tell, and the streams on either side of the valley road were red with Chinese blood. After the battle, there were counted in a space of two hundred yards the bodies of two hundred and seventy horses and two hundred and sixty men.This print by Kobayashi Kiyochika, titled "Banzai for Japan! Victory Song of Pyongyang" reflects some of this horror (or it does if you're able to peel away the jingoism just a little):

Two months after the battle, L.H. (Lillias) Underwood, in Fifteen Years among the Top-knots (quoted here), wrote:

According to native superstition that the city is a boat, and to dig wells would sink the boat, there were no walls in Pyeng Yang; but a large number of bodies of men and horses were lying in the river, polluting for weeks the only water supply. In this dreadful situation out brave missionaries remained and worked, and on October 17th Dr. Hall wrote the following cheerful words, 'We have very interesting services, the hymns of praise that less than a year ago brought cursing and stones are now listened to with delight, and carry with them a feeling of security similar to the sound of a policeman's whistle in New York. Comparatively few of the Koreans have returned to their homes, but every day brings fresh additions. Every day numbers of those who have returned and those from the surrounding villages and towns visit us. They buy our books and seem far more interested in the gospel than I have ever seen them before.'Hall's letter seems to confirm what I had suspected - that Pyongyang's ruin had helped spur the population to look more kindly upon the Missionaries who quickly returned. Before continuing with Underwood's account, it might be worthwhile to look a little more closely at Dr Hall. Most of the photos and biographical information about him in this post come from this blog (there are three pages).

William James Hall arrived in Korea in December 1891, a year after his future wife Dr. Rosetta Sherwood, who he married in 1892. Arriving in Pyongyang in 1894, Rosetta Sherwood Hall adapted Braille to the Korean script and began teaching blind girls, the first instance of 'handicapped' education in Korea. After Mrs Alice Moffett (Samuel Moffett's wife?) began a school for blind boys in Pyongyang in 1903, she opened the School for the Blind the next year.

In case you're wondering why William James Hall's future accomplishments aren't being noted, perhaps we should let Mrs. Underwood finish her letter:

Very soon after writing these words Dr. Hall returned to Seoul; the boat on which he came was full of sick Japanese soldiers. There were cases of typhus fever and army dysentery, the water was doubtless poisoned, and he reached Seoul, after numerous most trying vicissitudes, fatally ill with typhus fever. Quite early, articulation became very difficult, but every halting sentence spoke of perfect peace and joy, and almost his last words were, 'I'm sweeping through the gates.' Tears dim my eyes while I write, for we all not only loved, but reverenced Dr. Hall, and we felt he possessed a larger share of the Master's spirit than most of us.[...] Euopeans and natives alike testified to the same impressions of him, the same love for him, his sweet spirit drew all hearts to him, so that he was both universally loved and honored. [He died on November 24, 1894.]While he may have died young, his wife and son would continue to work as missionary doctors in Korea for decades to come.

Going back to the effect the Battle of Pyongyang had upon the efforts of missionaries there, Isabella Bird Bishop returned to Pyongyang in late 1895 or early 1896 after travelling further north, and made the following observations:

Christian missionaries were very unsuccessful in Phyong-yang. It was a very rich and immoral city. More than once it turned out some of the missionaries, and rejected Christianity with much hostility. Strong antagonism prevailed, the city was thronged with gesang [kisaeng], courtesans, and sorcerers, and was notorious for its wealth and infamy. The Methodist Mission was broken up for a time, and in six years the Presbyterians only numbered 28 converts. Then came the war, the destruction of Phyong-yang, its desertion by its inhabitants, the ruin of its trade, the reduction of its population from 60,000 or 70,000 to 15,000, and the flight of the few Christians.Also worth mentioning in Pyongyang at that time might be that

Since the war there had been a very great change. There had been 28 baptisms, and some of the most notorious evil livers among the middle classes, men shunned by other men for there exceeding wickedness, were leading pure and righteous lives. There were 140 catechumens under instruction, and subject to a long period of probation before receiving baptism, and the temporary church, though enlarged during my absence, was so overcrowded that many of the worshippers were compelled to remain outside.

On the Sunday I went with Dr. Scranton of Seoul to the first regular service ever held for women in Phyong-yang. There were a number present, all daemon worshippers, some of them attracted by the sight of a "foreign woman". It was impossible to have a formal service with people who had not the most elementary ideas of God, of prayer, of moral evil, and of good. It was not possible to secure their attention. They were destitute of religious ideas. An elderly matron, who acted as a sort of spokeswoman said, "They thought that perhaps God is a big daemon, and He might help them get back their lost goods." That service was "mission work" in its earliest stage.

The main street on my second visit had assumed a bustling appearance. There was much building up and pulling down, for Japanese traders had obtained all the eligible business sites, and were transforming the small, dark, low, Korean shops into large, light, airy, dainty Japanese erections, well stocked with Japanese goods, and specially with kerosene lamps of every pattern and price, the Delfries and Hinckes patents being unblushingly infringed.In In Korea With Marquis Ito (quoted here), Gerorge Trumbull Ladd, speaking in Pyongyang on April 7, 1907, said there were 1400 in his audience, "equally divided between the two sexes", divided by a screen.

It was said that there was enough of the population of the city attending Christian services at that same hour to make three congregations of the same size. The afternoon gathering for bible study and the evening services were even more crowded; so that the aggregate number of church-goers that Sunday in this Korean city of somewhat more than 40,000 could not have been less than 13,000 or 14,000 souls. Considering also the fact that each service was stretched out to the minimum length of two hours, there was probably no place in the United States that could compete with Pyeng-yang for its percentage of churchgoers that day. Yet ten years ago there was in all the region scarely the beginning of a Christian congregation.Three years before Ladd's visit, during the campaign of 1904 (during the Russo-Japanese war), Japanese troops had once again found themselves marching through Pyongyang - but this time, the absence of enemy forces there (and a growing awareness of the need for good P.R.), led to much better treatment of the city during the subsequent occupation.

Japanese Infantry await the completion of a pontoon

bridge before entering Pyongyang, March 1904

bridge before entering Pyongyang, March 1904

Koreans watching Japanese troops enter Pyongyang

Below is a photo of Pyongyang's missionary community taken around March 4, 1904, by R.L. Dunn (who, along with Jack London, had reported on the Japanese advance northward), which makes obvious that the growth of Pyongyang's (Korean) Christian community was accompanied (or preceded) by a large growth in the number of missionaries there - a far cry from the previous descriptions of mission efforts we've seen from before the Sino-Japanese war (Photos taken from here).

It seems to me to be very difficult to explain the sudden growth of Pyongyang's Christian community (or of its development in other aspects) without examining the effect of its destruction during the Sino-Japanese War.

Prior to the war, Bishop describes it as " a very rich and immoral city[...] the most prosperous city in Korea." "[T]he city was thronged with gesang, courtesans, and sorcerers, and was notorious for its wealth and infamy". Creelman spoke of "the dancing girls of Ping Yang, renowned throughout Asia for their grace and beauty", while Elizabeth McCully noted that a house purchased by the missionaries "had been used as a home for dancing girls". In the minds of these good Christians, as they speak of an "immoral city" full of "infamy" and "evil", Pyongyang seemed to have been perceived as a modern Sodom and Gommorah (which makes you wonder how its destruction during the war was perceived). As Bishop put it, this was all before "its desertion by its inhabitants, the ruin of its trade, the reduction of its population".

The most obvious effect the battle had upon the city was "the reduction of its population from 60,000 or 70,000 to 15,000". Bishop also mentioned a figure of 80,000 for Pyongyang's pre-war population; whatever the exact number, a year later in 1895, it seems that only a quarter of the population had returned. Twelve years later, in 1907, Ladd gives the population of the city as 40,000, which is still only 2/3 of its population in 1894 (if a figure of 60,000 is accepted). One can only guess at how this disrupted the social fabric of the city and ruined its economy; pondering this might lead one to understand how Christianity might suddenly seem more palatable, especially when those preaching it are also opening schools and healing people.

As Dr Hall put it two months after the battle, "Comparatively few of the Koreans have returned to their homes, but every day brings fresh additions. Every day numbers of those who have returned and those from the surrounding villages and towns visit us. They buy our books and seem far more interested in the gospel than I have ever seen them before." Bishop's description of the city's first church service for women provides a fascinating look at the participants' perception of deities, as well as their reasons for wanting to explore Christianity in a looted and ruined city: "They thought that perhaps God is a big daemon, and He might help them get back their lost goods." As Bishop put it succinctly, "That service was "mission work" in its earliest stage."

Beyond the effect on missionary work the city's ruin and desertion had, Bishop mentions another change: "Japanese traders had obtained all the eligible business sites". The degree to which, prior to the war, a Japanese presence existed in Korea outside of Busan, Wonsan, Chemulpo (Incheon) and Seoul I'm not sure of. After 1894, of course, Japanese people (and soldiers) were able to move about with much more ease. I'm not certain if there were any Japanese living in Pyongyang prior to the war, but after the war it seems their presence was becoming much more prominent, as they bought up prime land in a city their troops had helped lay to ruin (and after the fighting had ended, remember). Pyongyang, in regards to its growing Japanese population, could likely have simply served as a microcosm of the rest of the country, as Japan consolidated its control and prepared for its eventual war with its other rival, Russia. Russia's reappearance in Pyongyang in 1945 would, of course, set in motion events that would lead to Pyongyang's destruction once again - along with the (apparent) destruction of the Christian faith there.

Of further note regarding Pyongyang and missionaries: this page comments on the influence on music in Korea the missionaries had, due to their music lessons. A bibliography of writing about (and by) missionaries in Korea can be found here. Turn-of-the-century (or earlier) photos of Pyongyang and Gaeseong can be found here. A 1946 US military map of Pyongyang can be found here, while a current map (and metro map) of contemporary Pyongyang can be found here.

Also, on a vaguely related yet fascinating note, a school in Oregon was named Pingyang after the battle in 1894, and was eventually bombed and destroyed a few years later. The story can be found here.

Just a quick note to say how much I enjoy the old Korean photos you've posted over the years. If you ever succumb to creeping whatsthepoint-itis, please leave the blog archive up!

ReplyDelete