In the book Contentious Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea's Past and Present, there's an interesting essay by Don Baker titled "Victims and Heroes: Competing Visions of May 18". For the curious, Baker was in Kwangju the day after the military retook the city, and the story of his escape from the city, along with Linda Lewis, appears in her book Laying Claim to the Memory of May. (A quick update - in his review of this book, Baker refers to his connection to the city).

At any rate, Baker's essay is influenced by Paul Cohen's book History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth, which distinguishes between the reconstructions of events by historians, contemporary accounts, and, as Baker describes it, the "perspective generated by the significance ascribed to [an] event." He continues:

When later generations draw lessons from a significant historical event...they change the way that event is viewed and discussed. Cohen calls this third perspective, refashioning the past to meet the needs of the present, the construction of a "myth"... [T]he mythical retelling of an event is designed not so much to relate what actually occurred as it is to encourage certain sentiments, arouse certain emotions, serve certain political functions, or fulfill certain psychological needs.He goes on to describe how such myths isolate or focus on certain aspects of an event, and uses this framework to look at how popular narratives of the Kwangju Uprising in different media illuminate either the tragedy of the victims, or the heroism of those who rose up against those who brutalized them. Those narratives published in the years directly after the uprising (mostly short stories or poems) tended to focus on the victims, while some later narratives focussed on heroism of the uprising.

This essay is well worth reading (in fact, the entire book is), but the reason I'm going into a discussion of it here is that Baker's description of these short stories made me aware of their existence and prompted me to look for English translations of them on the internet. I managed to find a number of them, and so link to them I do.

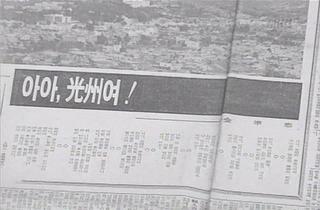

Kim Jun-tae's 1980 poem Kwangju, Cross of Our Nation, was published soon after the uprising occurred; he was dismissed from his high school teaching post for publishing this poem (another translation can be found here). That's a picture of the poem as it was published in the Jeonnam Maeil Sinmun at the top of this post.

Im Cheol-woo's Spring Day (1984), about a character who feels guilty over his friend's death during the uprising, can be found here, while another story involving Kwangju by Im Cheol-woo, A Shared Journey, can be found here (scroll down to the very bottom).

Choi Yun's There a Petal Silently Falls (Part 1 ; Part 2) was the novella upon which Jang Sun-woo's 1996 film 'A Petal' was based.

Kong Son-ok's short story Parched Season (1993), depicts the lives of marginalized figures who are survivors of the Kwangju Uprising.

Parched Season and Spring Day (and 3 other stories about the Korean War) are discussed in the essay Remembering Trauma: History and Counter-Memories in Korean Fiction by Susie Jie Young Kim.

On the topic of visual depictions of the uprising, Hong Seong-dam's woodblock prints can be found here. Hong made most of the prints shortly after the uprising. In 1989 he was arrested under the National Security Law and sentenced to 7 years in prison, of which he served three. Hong's main offense was to have sent to Pyongyang, North Korea a photographic slide of a large mural that he had painted. He discusses the torture he underwent in prison near the bottom of this page.

Numerous Photos of the uprising can be found here, while documentary footage can be downloaded here (about 2/3 down there are 3 files listed; click on 영상1, 2, or 3 or right click and 'save as' to save. I believe the first file is a music video which contains footage from the second and third files).

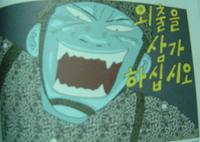

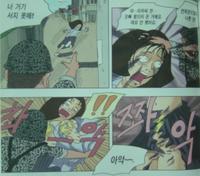

Baker's essay mentions that in some cases, as the idea of who the victims were evolved, certain narratives considered the soldiers to be victims as well, as they were forced to carry out such violence. The protagonist of the film Peppermint Candy is portrayed as a person devastated by his role in the violence, for example. A 200 page manhwa (comic book) I picked up in Kwangju during the 25th anniversary of the uprising has none of this, however; the soldiers are depicted as the embodiment of pure evil, such as in the photos below, one of which depicts a soldier stripping a teenage girl (which was common practice for prisoners of either sex), and later, raping her.

This girl, whose name, Jo Hyeon-jeong, is clearly pointed out, isn't just meant to represent one of many victims; the comic depicts what happened to specific people. This makes clear that people in Kwangju, and the narratives that continue to be produced there, view what happened in much more personal terms than those from other regions of the country, for obvious reasons. When I watched high school students re-enact the shootings of May 21, two of the students I talked to told me proudly that their fathers had taken part in the uprising. The event's relationship with the city it occurred in is something Linda Lewis discusses a great deal in her book, a book I recommend most highly.

There are at least 6 or 7 documentaries (in Korean) about Kwangju on emule. Try searching for 518, 광주, or 5-18 and they should turn up. Some have contemporary footage, while others have interviews with surviving citizen's army members, former paratroopers, and foreign journalists.

From a different point of view Kwang Ju May 1980. I was there. Just one week short of my 21st birthday. Very chaotic. Seemed surreal at times, but was most real in the end. I remeber that week always. gdajr2@aol.com

ReplyDelete