My first response upon reading this (the English version did not make clear that he was a POW Camp guard), was to think of this recent article, which spoke of how General Kim Paek-il, who convinced the US military to save 100,000 refugees during the Heungnam evacuation of late 1950, was later targeted by anti-Japanese activists (inspired by Roh Moo-hyun's Presidential Committee for the Inspection of Collaboration in Japanese Imperialism), according to whom "Kim was involved in Japan's brutal crackdown on Korean independence fighters in the Manchuria region in the 1930s," and they erected a monument criticizing him next to his statue. Taking things further, in May some progressive lawmakers "called for a bill to have the remains of Kim and other Korean 'colluders' during the Japanese colonial period removed from the national cemetery," and to block the burial of Korean War hero Paik Sun-yup. There is no indication that such a bill would have any support, and I hope it doesn't. Considering Korea's long history of disinterring political enemies (perhaps they could just do as Yeonsan-gun did and simply behead the buried remains?), you would hope such officially-mandated desecration would remain in the pre-modern era where it belongs.

Thinking of the above example, I couldn't help but wonder if those lawmakers and activists would also want to put a memorial next to Komarudin's grave calling him a "pro-Japanese traitor," since that's what they seem to consider any Korean who joined the Japanese army to be. But then, after consulting the Korean-language articles, I realized he was a POW Camp guard, and, well, anti-Japanese activists - particularly those in the employ of official truth commissions - have demonstrated profoundly lenient attitudes toward POW Camp guards who mistreated Allied prisoners so badly that they were convicted of war crimes.

According to Utsumi Aiko’s “Korean ‘Imperial Soldiers’: Remembering Colonialism and Crimes against Allied POWs,” in the 2001 book Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s), serving in the Japanese military in the 1930s and 1940s were 17,000 Volunteer soldiers (through a system begun in 1938) and around 110,000 soldiers who were conscripted in 1944 and 1945. There were also around 120,000 civilian employees of the military, which included POW Camp guards.

At the end of World War II, 23 Koreans were executed for war crimes, and 125 were imprisoned. Of the 148 in total, 3 were soldiers and 16 were translators, and “of the 3,016 Korean men conscripted to work as prison guards 129 were found guilty of war crimes.”

These war criminals were transferred to Sugamo Prison in Tokyo to serve out their sentences, but while Japanese serving out their sentences there got government benefits (for, say, injuries incurred during their service during the war), Koreans, since they were no longer Japanese citizens, did not. When the Korean war criminals were released, those who continued to live in Japan formed the Association for the Mutual Advancement of Korean War Criminals and sought compensation from the Japanese government (as described here).

What needs to be remembered, however, is that many POW Camp guards were not conscripted, but volunteered. According to an unpublished paper of mine about Japanese POW camps in Korea, the announcement of the conscription system for Koreans - to begin in 1944 - was announced on May 9, 1942.

In addition to this, on May 22, 1942 a system allowing Koreans to apply to be prison guards for American and British prisoners of war was announced. The Maeil Sinbo reported the “once again glorious news,” coming two weeks after the conscription system announcement, that “as imperial subjects our brethren from the peninsula will also bear the heavy responsibility of national defense” by guarding prisoners overseas, though some would be employed in Korea. Such lofty language appeared a day later when it was reported that “a sublime path to cooperate in building the southern part of the co-prosperity sphere has opened for the youth of the peninsula who will be employed by the military.” The reason for the system was made clear: “Six months have passed since the war to destroy the Americans and British was begun last December 8, and already the number of enemy prisoners has reached 340,000.” Applicants needed to be between the ages of 20 and 35, have robust bodies and no diseases, have completed at least 4th grade in elementary school, and had to be able to carry on everyday conversation in Japanese. The Maeil Sinbo spent weeks covering the application, testing, and instruction process of these young Korean men[.]

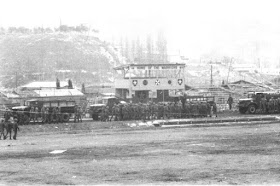

The first day of applications. (Maeil Sinbo, May 26, 1942)

Taking an employment test. (Maeil Sinbo, June 6, 1942)

(Maeil Sinbo, June 10, 1942)

Farewell ceremony. (Maeil Sinbo, June 13, 1942)

It's said that at least some of these POW guards were conscripted, but the earliest to be sent had to apply and pass written and physical tests to become guards.

A nuanced examination of how Koreans were remembered in POW literature, and of the POWs awareness of the low status of their Korean captors vis-a-vis the Japanese - while at the same time recalling their casual brutality - can be read here.

Now, in November 2006, under - once again - Roh Moo-hyun's presidency, the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Colonial Rule, "confirmed," as the Donga Ilbo put it, that "Korean POW camp guards were sacrificed without a proper trial." It examined the cases of 86 of the 148 Koreans convicted by the Allies of war crimes and cleared 83 of them, or as the Hankyoreh put it, it "recognized them as victims and removed the stigma of them being war criminals." In other words, a Korean government commission unilaterally ruled that the judgements of the Allied War Crimes Tribunals after WWII no longer applied to these Koreans. It should be noted that 12 of the 86 applications made to the truth commission were from the relatives of Koreans who were executed for war crimes. The commission decided that the Korean war criminals, who "unavoidably" became POW camp guards to avoid the Japanese draft were burdened with responsibility for the abuse of Allied POWs, and so had to suffer the "double pain" of forced mobilization and becoming a war criminal.

Lee Se-il, head of the fact-finding investigation team, said, "As a result of analyzing the military prosecutor records of 15 Korean prisoner-in-law recently obtained from the National Archives of England, we were able to confirm that the conviction was made without clear evidence." (A few months later the Hankyoreh examined some of these cases and interviewed a former guard who had been sentenced to death. More on his case, and his activism in seeking redress from the Japanese government, can be found here.)

What annoys me is that one hears sympathy for men who would be called collaborators if they had been working in prisons that held fellow Koreans during colonial rule. Their prisoners were (largely) white, however, so they are afforded as much understanding as possible. And they get to be called “victims.”[He follows this with a more nuanced discussion at the link.]

That mistakes were made when some of these POW Camp guards were judged, I would not be surprised. That mistakes were made in over half of the cases, including half of the cases that led to executions? That seems rather unlikely. But considering the fact that the guards suffered "double pain" at the hands of Japanese and Western imperialists, the two bêtes noires of National Liberation-style Korean progressivism, perhaps the desire to beatify them with the hallowed status of "victim," and, while they were at it, to declare the decisions of Allied tribunals null and void and therefore expand Korean sovereignty backwards in time, was too tempting to pass up.

On May 26, the Segye Ilbo published the following report that reveals that the work begun 14 years ago continues today:

Korean and Japanese scholars work together to recover the honor of Korean POW camp guards who became war criminals.Well, it's nice to see Koreans and Japanese working together, I guess. Still, the feeling you get from reading about "Korean POW camp guards who became war criminals" or who "were branded as war criminals" or about "how the situation of war turned them into war criminals" is that the reason they became war criminals was because of unfair actions taken by the Allies, and not because these Koreans abused Allied prisoners. It's certainly something to think about the next time you hear the Korean government decry Japan's refusal to take responsibility for its past.

On May 26, the Ministry of Public Administration and Security-affiliated Foundation to Support Victims of Japanese Imperial Forced Labor announced that it will hold an international academic conference to re-examine the "reality of forced mobilization of Korean POW camp guards" who were dragged to Japan during the period of resistance to Japan.

On May 28th, the Foundation to Support Victims of Japanese Imperial Forced Labor will hold an academic conference on the theme of “International Comparisons to Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan' at the ENA Suite Hotel in Seoul. This academic conference is looking to commemorate the Korean POW camp guards forcibly mobilized by the Japanese imperialists and to restore their honor. The Korean POW camp guards were sent by Japan to places like Thailand, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Indonesia by Japan, and faced with prisoners, after the Pacific War they were branded as war criminals. In 2006, they were first recognized as victims by the "Truth Commission for Victims of Forced Mobilization Under the Japanese Empire."

Five Korean and Japanese scholars will give presentations. Arimitsu Ken, an invited researcher from the Waseda University International Reconciliation Research Center will present “The progress and present of the compensation issue for Chosen soldiers and civilians after the war,” and Professor Okada Taihei from Tokyo University Graduate School’s Department of Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies, will present "Sexual Violence by Japanese Forces in Visayas, Philippines.''

As well, Kim Jeong-suk, a researcher at Sungkyunkwan University's East Asian History Research Institute, will present "Cases and Lives of Korean POW camp guards under the Japanese Empire," and Yoo Byeong-seon, a lecturer at the Faculty of Liberal Studies at Korean Traditional Culture University, will present "The current status and anti-Japanese activities of the Korean POW camp guards in Indonesia at the end of the Japanese Empire."

Kim Yong-deok, president of the Foundation to Support Victims of Japanese Imperial Forced Labor said, "Through this academic conference, how the prisoners of the Korean prisoners were mobilized and how the situation of war turned them into war criminals will be re-examined within the international community." "Even now, the way needs to be made clear to restore the honor of all those who suffered from Japanese imperialism."